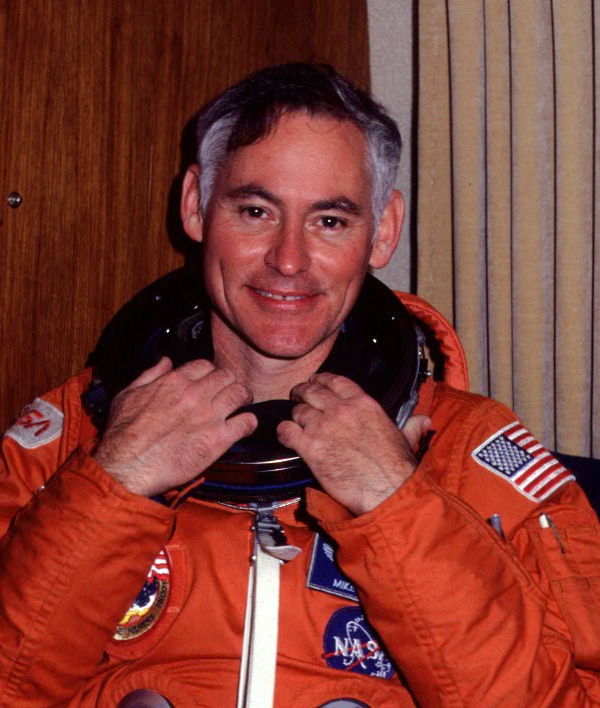

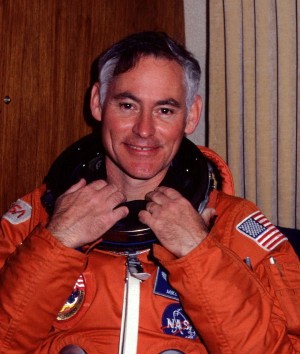

by R. Mike Mullane (NASA Astronaut, Ret.) © 2017 All Rights Reserved

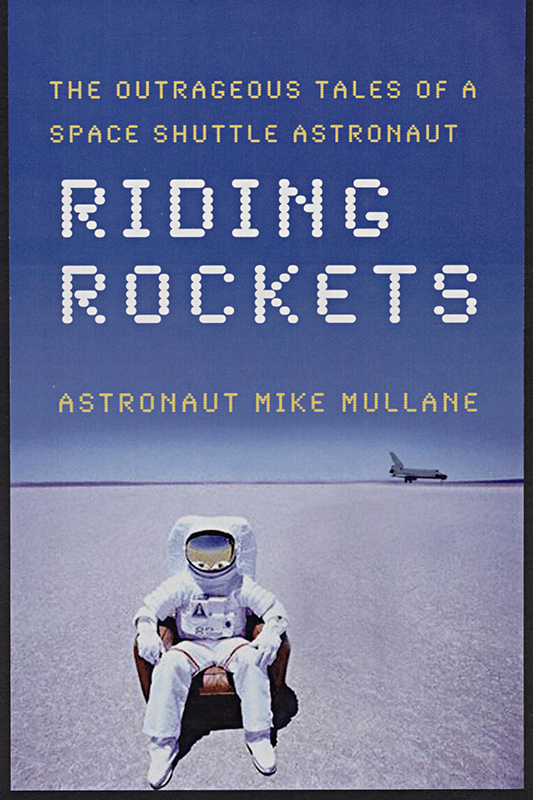

Author, Riding Rockets, the outrageous tales of a space shuttle astronaut.

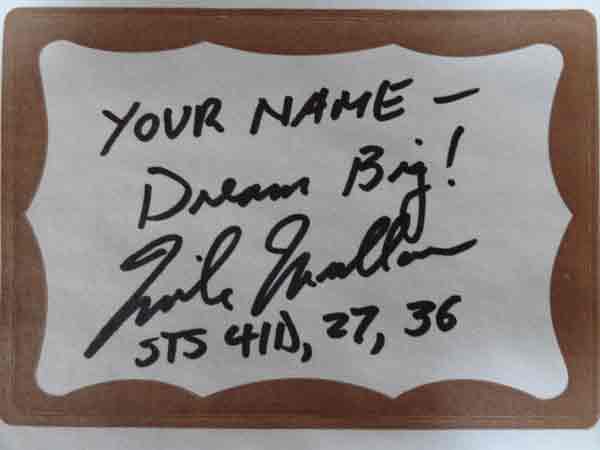

Autographed copies can be ordered via Mullane’s website store: www.MikeMullane.com

“Ladies and gentlemen, please welcome a true American hero…Astronaut Mike Mullane!”

Applause carries me to the stage and I start my program.

Whenever I hear the word ‘hero’ in my public introductions, I wince in discomfort. By what measure am I a hero? By what measure is anybody a hero?

I can easily define the outer limits of heroism: the soldier who covers a grenade with his/her body to protect the rest of the squad; the firefighter who rushes into a burning building to save the occupants; the police officer who takes a bullet to protect a civilian; the physicians and nurses who volunteer to care for victims of war despite the battlefield dangers to themselves. Ordinary members of the public have also risen to similar levels of heroism, most recently seen in the example of complete strangers protecting others in the Las Vegas mass shooting. Unquestionably, someone who places their life in grave danger to save another, is a hero.

On the flipside, I find it easy to exclude those who are frequently bestowed the honorific of ‘hero’ but are not: Hollywood celebrities and athletes.

But, between those boundaries, defining the qualifications to be branded a ‘hero’ becomes more difficult. Take myself for example.

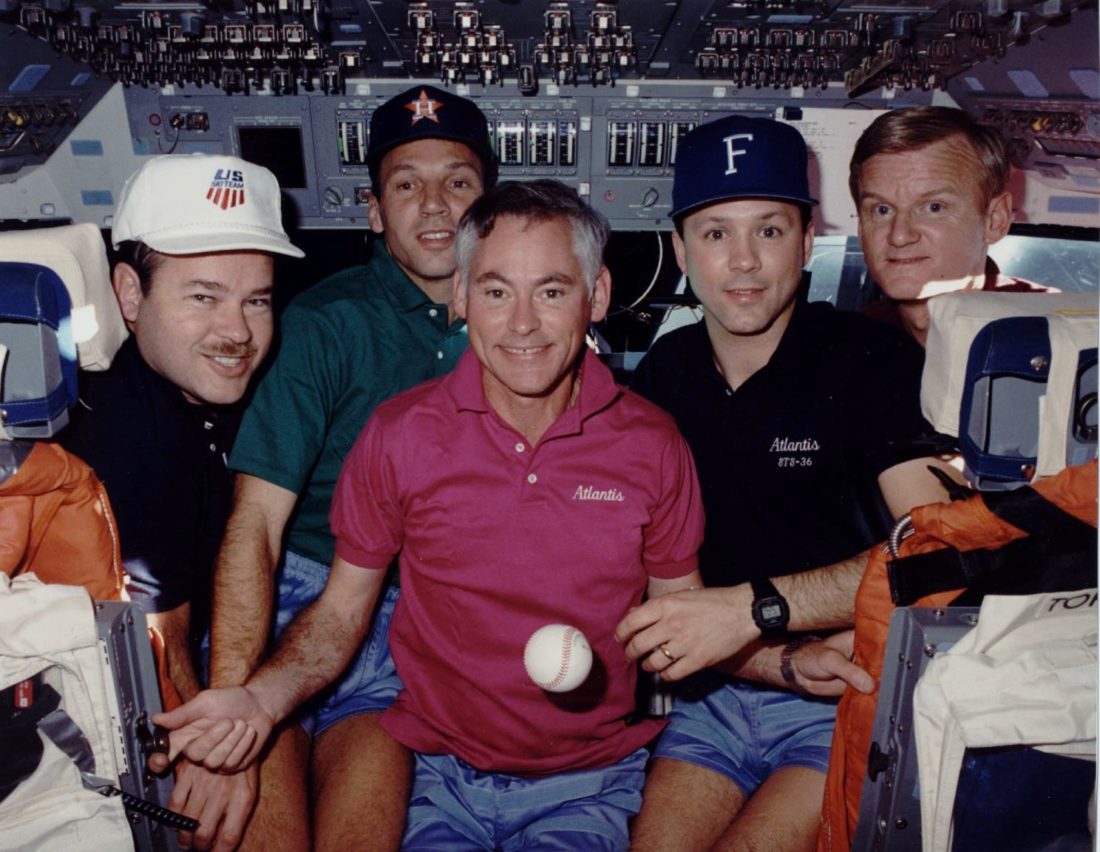

Am I a hero because I took the risk of flying into space three times? In my opinion there must be an element of selflessness for an act to qualify as heroic and that was certainly not the case in my astronaut career. Here’s an excerpt from my memoir, Riding Rockets, which reveals my motivation for assuming the risk of riding four million pounds of propellant into space:

I was as scared as I had ever been in my life. But at that moment, if God had appeared and told me there was a 90 percent probability I wasn’t going to return from this mission alive and had given me an opportunity to jump from that crew van, I would have shouted, “No!” For this rookie flight, I would take a one in ten chance. I had dreamed of this moment since childhood. I had to go.

Clearly, I strapped into the cockpit of a shuttle because I wanted to. There was nothing selfless about that act. In fact, my subsequent missions could be considered acts of selfishness, given the extreme stress those post-Challenger missions placed on my wife and children. Therefore, in my opinion, my astronaut title does not number me among the ranks of ‘true American heroes.’

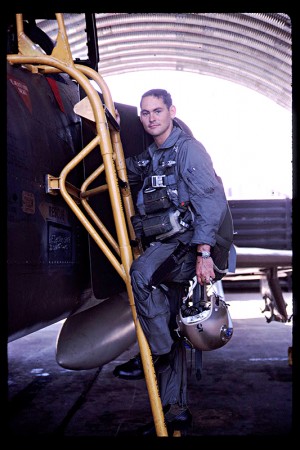

What about my military service, specifically my service in Vietnam? Surely, that’s a ticket into the pantheon of American heroes, isn’t it? Maybe. There were certainly moments of selflessness in my war tour, times when I wanted to be anywhere other than in that cockpit…as in every night mission into mountainous terrain.

So, I could accept a nod into the door of the Palace of Heroes as a veteran of that action, but only for one of the cheap seats waaaaay in the back. I read too much American history to compare my 134 combat missions to what many men and women have faced in their combat service in our nation’s wars. Read about the slaughter in the air war over Europe in WWII; running into the steel hail of Iwo Jima; being in a submarine under depth charge attack. Read about being whistled out of the trenches in WWI or retreating from the Chosin Reservoir in Korea. I could never accept a position next to those who demonstrated this type of heroism in their combat service. It’s the back ranks for me.

So, I could accept a nod into the door of the Palace of Heroes as a veteran of that action, but only for one of the cheap seats waaaaay in the back. I read too much American history to compare my 134 combat missions to what many men and women have faced in their combat service in our nation’s wars. Read about the slaughter in the air war over Europe in WWII; running into the steel hail of Iwo Jima; being in a submarine under depth charge attack. Read about being whistled out of the trenches in WWI or retreating from the Chosin Reservoir in Korea. I could never accept a position next to those who demonstrated this type of heroism in their combat service. It’s the back ranks for me.

From these comments, it seems my definition of heroism is very narrow, i.e., selflessly putting oneself in grave danger to protect country, family and community. And I certainly believe those criteria are sufficient to be labeled a hero. But are they necessary?

No, I do not believe that. For example, I have frequently said adopting a child is a heroic act. Anybody who has raised a child knows of the immense sacrifice required. I cannot imagine willingly undertaking that burden for another person’s child. Similarly, I find heroism in those who donate organs to strangers. Or those who spend their lives caring for the physically or mentally handicapped. Or, the handicapped themselves who rise above their disabilities to accomplish goals that would be challenging even to the whole-of-body population.

Here, I have a personal example. My dad was rendered paraplegic by polio in 1955 at age 33. He spent the rest of his life confined to a wheelchair. But he and my mom refused to wallow in self-pity and continued their mission of raising six children.  It was this experience that makes it so easy for me to answer a question I sometimes hear, “As a child, who were your heroes?” It’s a no-brainer, “My mom and dad.” With only two good legs between them, they did a better parenting job than do many couples with everything working for them.

It was this experience that makes it so easy for me to answer a question I sometimes hear, “As a child, who were your heroes?” It’s a no-brainer, “My mom and dad.” With only two good legs between them, they did a better parenting job than do many couples with everything working for them.

If I considered it for a longer period, I could probably come up with more examples of what I would categorize as non-life-threatening heroic behavior. But, in doing this, I have now made my definition of heroism relative. I’ve expanded the criteria to include things involving significant personal sacrifice for the primary reason that I wouldn’t do them.

So, what are the qualifications to be stamped a hero? In the end, I guess it’s how we, as individuals, define those qualifications. It calls to mind a comment by United States Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart in 1964. While struggling with a case that centered around the definition of pornography, he remarked,

“…I could never succeed in [defining pornography]. But I know it when I see it…”

That’s it. I can’t define heroism. But I know it when I see it. And do I see it in myself? Is Mike Mullane a ‘true American hero’, as I’ve heard in those stage introductions? I will never believe that. But, if I am, it exists only within my military service and NOT in my years as an astronaut.

Who’s a Hero?

by R. Mike Mullane (NASA Astronaut, Ret.) © 2017 All Rights Reserved

Author, Riding Rockets, the outrageous tales of a space shuttle astronaut.

Autographed copies can be ordered via Mullane’s website store: www.MikeMullane.com

All photos, other than personal family photos are courtesy of NASA.