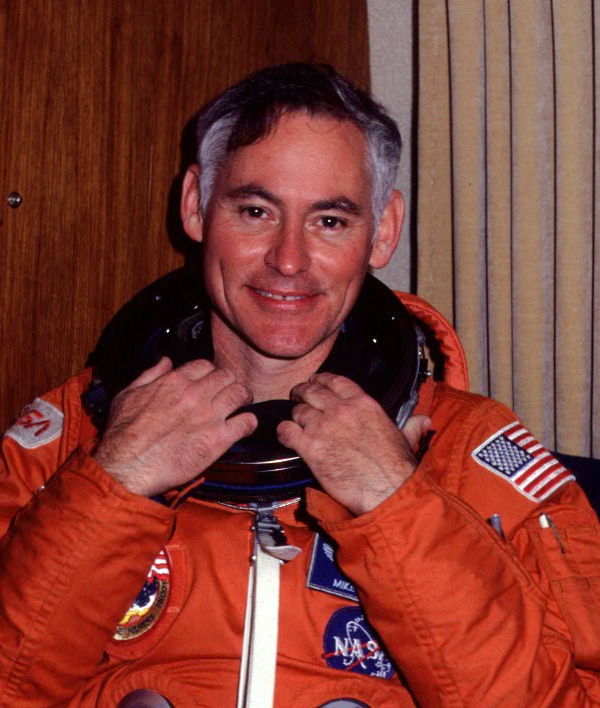

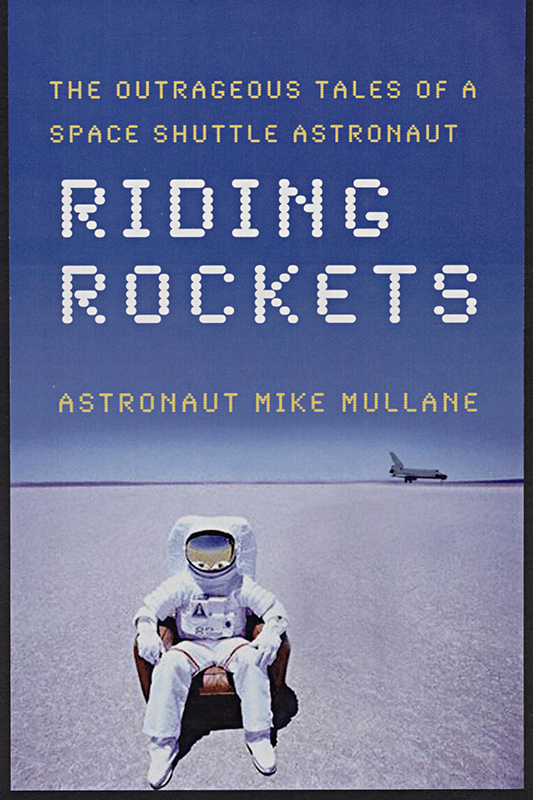

by Astronaut Richard ‘Mike’ Mullane, Copyright 2019 by Richard Mike Mullane, all rights reserved. Author of Riding Rockets, The outrageous tales of a space shuttle astronaut. Autographed copies of Riding Rockets can be ordered from the Online Store on this website. Photos are from author’s personal family archives, except the space shuttle launch photo, which is a NASA public domain photo.

“Sir, would you like a seat?”

I turned from my phone to see this question was being asked of me. I was a straphanger in a crowded rental car bus and a man had risen from his seat to offer it to me. Obviously, his parents had raised him to respect his elders. In this case, the 74-year old elder he was respecting, was me. Ouch!

The irony of the question came in a flash. It was being asked by a 30-ish man who clearly didn’t hit the gym very often, perhaps never. I, on the other hand, was a lean, conditioned geriatric (if there is such a thing) just returning from three days of backpacking in the Colorado mountain wilderness. If anybody on that bus was in need of a seat, it wasn’t me.

My parents raised me to acknowledge random acts of kindness and I graciously declined his offer.

The experience of being treated as a geriatric (not my first) prompted me to consider, Is that why I do so much backpacking; because it qualifies me as ‘young’, even if I don’t look it? (I’m on track to log over 400 miles of backpacking this year.) Certainly, that vanity was present in my thoughts. In that regard, I have plenty of company. There are legions of others who practice their ‘things’ to keep from being perceived as middle-age or senior or geriatric or just plain old: the gym rats, the hot-Yoga crowd, the mountain bikers, the marathoners, the triathletes, the senior Olympics geezers, etc. I know of one geriatric who saw enduring the ‘rigors’ of first-class world travel at his advanced age, as his fountain of youth. All of us think, I can’t be old, if I can still do XYZ!

But, if that’s all there is to our ‘things’, i.e., to earn some bizarre bragging rights over the couch-potato crowd, who probably couldn’t care less, then I pay a huge price in discomfort to earn mine. And I’m not just talking about the agony of humping up 45lbs into the rarified air of the Colorado high country.

It won’t take long on a hike into the wilderness to realize the photos in the catalogues of smiling campers sitting in chairs around a blazing fire eating smores and drinking cocoa, are complete BS. To walk into the wilderness is to abandon a couple thousand years of evolutionary ease…including chairs, beds, toilets, kitchens, showers, and cell phones. If there was truth in advertising, those catalogues would include a photo of a wilderness backpacker squatting like a Cro-Magnon, while grunting a bowel movement into a hole. Oh…and another photo depicting him/her zip-locking their used toilet paper into a plastic bag to pack out. I, and other responsible backpackers, do that. Leave no trace is not just a suggestion to us. It’s a commandment. The only other times I’ve been that intimate with my waste disposal was on my three space shuttle missions.

Wilderness living is living down and dirty. You’ll hike in rain, hail, snow or broiling sun…sometimes in all of these conditions on the same trip. You’ll become indifferent to wearing the same clothes for multiple days. The sight of dirt under your fingernails won’t elicit a shrug.

You’ll sleep on the ground on a thin air-mattress using a bag of your dirty clothes as a pillow, not caring about the smell of your own body odor infused in those clothes. Your meals will be reconstituted dehydrated food (another similarity to spaceflight) and you will eat sitting on a rock, log or the ground. You’ll become obsessed by water. By far, it is the densest thing to carry (one-liter weighs over 2 lbs) and you will need a lot of it. So, you must plan carefully to know where to find it…and will grow weary of hand-pumping it through a filter. (To drink unfiltered water is to be exposed to diarrhea-inducing waterborne bacteria.)

And wilderness hiking is dangerous. It’s called ‘wilderness’ for a reason. It’s ‘wild’ and occupied by wild things. In the mountains of the American West you are trespassers in the domain of two big carnivores: mountain lions and bears. But the risk of attack from these animals is extremely small. (The wildernesses of New Mexico and Colorado have only black bears. Further north in the Rockies are grizzly bears, which are much more dangerous.) In my decades of hiking I’ve never seen a mountain lion, though experts on those creatures say they are watching you on virtually every western wilderness hike. The few black bears I’ve encountered turned and ran from me. They are timid creatures, unless you have the misfortune to come across a mother with cubs. Then, you’re in trouble.

When hiking at altitudes below 8000 ft in the desert mountain west, there’s a much smaller and stealthier creature posing a very real threat to your life…rattlesnakes. Every year, I come across a few of these lethal reptiles. And unlike the young of big predators, even the smallest rattlesnake has the venom capacity to kill you. Trust me, there are two moments you’ll never forget in your life: the first time you see a line of anti-aircraft tracers just missing your aircraft and the first time you hear the sudden, buzzing-hiss of a rattlesnake and find the coiled, tongue-flicking bastard only a yard from your foot. In both situations you’ll experience the ultimate level of fear…a cold shot of piss to the heart, an expression used in Vietnam to describe any near miss. A rattlesnake can kill you just as certainly as enemy fire, particularly if you are many hours from help, which is the reality of wilderness hiking. Even with timely medical assistance, there’s a risk you will lose the venom-injected limb to amputation.

But, when I hike in the mountain wilderness areas of Colorado (my favorite location), I’m at elevations that are well above rattlesnake habitats. On these trips it’s Thor’s wrath that I fear…lighting. As it is with water, backpackers become obsessed with the weather. Just a single puffy cumulus cloud will bring a tickle of fear. You learn early as a hiker (you’re a fool, if you don’t) those embryonic wisps of water vapor can be a life-threatening thunderstorm within an hour. Virtually every summer during prime thunderstorm time, there are reports of lightning fatalities in the mountain west. On two occasion I have come across evidence of its immense power. On one 14,000 ft peak I stepped through a detritus of granite shrapnel…the result of a recent lightning strike on a summit boulder. On another occasion, I found large splinters of fresh pine on a forest trail. That mystery was solved when, a few moments later, I came to a 50-ft tall ponderosa pine, split down the middle by a lightning strike. Had anybody been within 20 yards of that tree at the time of the strike, they would have been impaled by jagged, hand-sized shards of white pine.

And the danger doesn’t stop with animals and weather. The very nature of wilderness hiking exposes you to injury and death through falls, avalanches, dehydration, getting hopelessly lost, and hypothermia. Again, few climbing seasons pass, when there isn’t a report of at least one climbing/backpacking death.

I had my close call. I was nearing a 14,000 ft summit when the terrain became dangerously steep, forcing me to turn back. This was my climbing moment of a cold shot of piss to the heart. My extreme focus on those final 200 ft of elevation had blinded me to just how steep my descent would be. I was trapped. I couldn’t safely continue up or climb down. It was only by the grace of God that I was able to shed my encumbering pack, lower it by a cord to a retrievable location, and slowly inch my way to safer terrain…all the while in a full-body rock-clutch every bit as intimate as a lover’s embrace. That was the trip in which the very real danger of summit fever was revealed to me. Mountain climbing legend, Ed Viesturs, said it best, “Getting to the top is optional. Getting down is mandatory.” I remain mindful of those words to this day.

Early in my backpacking I learned the hard way that the greatest risk of falls is on the descent portion of a hike; not the ascent. One descent-fall produced a bloody face-plant into rocks; another, a humiliating fall into a cactus. The latter ended with me naked on the bed while my wife used a magnifying glass and tweezers to pull cactus spines from my ass. We laughed together at how our vows ‘for better or worse’ capture some strange ‘worse’ situations…like the extraction of cactus needles from a spouse’s ass.

Those, and a few other non-life-threatening falls early in my backpacking advocation, opened my eyes to be ever vigilant to the dangers of complacency. Before taking a single step downward, I force myself to set aside the distraction of the high that comes with a successful summit and get my head back in the game.

Even health events, which can be easily and quickly treated in urban settings, can become death sentences in the wilderness. I once encountered a young man who shared his wilderness near-death experience. While on a solo hike he suffered a ruptured appendix, eventually collapsing in unconsciousness. He would have died but for another hiker who came upon him and who just happened to be carrying an emergency satellite beacon. (I carry one of these devices; another marvel of the space program.) His rescuer was able to send an SOS into the 911 system and within an hour a helicopter was plucking him from the peak.

So, the ‘thing’ I practice to excuse myself from the ranks of the old, is dirty and dangerous. It’s also damned expensive. When I’m fully kitted-out for an overnight backpacking trip, I’m a grunting, wheezing, sweating REI catalogue. Take a look at any page in one of these catalogues and you’ll understand what I mean by ‘expensive’.

To be a wilderness backpacker is to embrace sweat, dirt, danger and expense. When I write it down, it does seem borderline insane…until you consider the payback.

First, there are the health benefits of extreme exercise. My key metrics of cardio-vascular health, i.e., weight, BMI, blood pressure, resting heart rate, lung capacity, etc., would put me in the top fraction of one-percent of the geezer population and probably in the top percentile of the general population. I’m a chiseled geezer…a scary mental image, to be sure! (There’s grim irony here. I’ve been diagnosed with plaque in my arteries, the definition of heart disease. All of us millions with similar diagnoses have an ever-present bullet aimed at us. In my case, if the bullet ever fires, I will kill me in perfect health!)

But the marathoners, triathletes, gym rats and Peloton enthusiasts can make the same claim to exceptional cardio health…and they do it without the danger and the troglodyte living conditions of backpacking. So, why don’t I just buy a stair-stepper and climb to the Moon?

One of the reasons is the intense and lasting endorphin rush that comes during those final steps onto a summit, when the world falls away at your sides and 100-mile vistas are revealed in every direction. The first time you experience that, you’re hooked for life. There’s nothing else like it. Sure, crossing the finish line of a marathon or completing a triathlon provides the high that comes with great athletic achievement. But I believe summitting a mountain has the greater effect. Why? Because it’s a solo achievement. (I refer to the type of climbing I do, which is not technical and requires no support.) In climbing mountains nobody comes aside me to help with pacing or to offer me an energy drink. No spectators cheer me onward. If I fall behind in exhaustion, I cannot seek solace in the company of others suffering the same fatigue. No friends or loved ones embrace me at the finish. When I reach a summit, it’s truly a solo moment. That doesn’t sound like much of a payback, but it is.

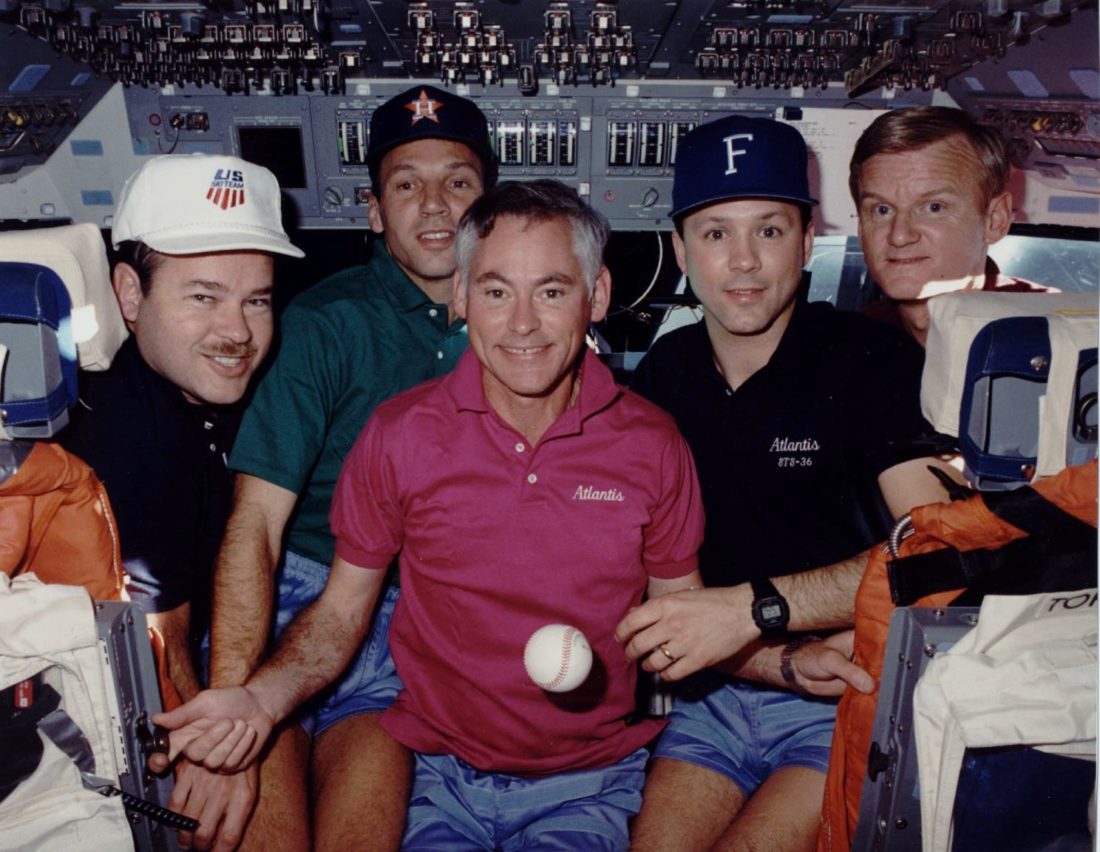

Throughout my life, I’ve had opportunities to participate in some amazing things, to reach summits of a different form: graduating from West Point, qualifying as an Air Force crewmember in a Mach 2 jet, and reaching earth orbit as a shuttle astronaut. And I’ve taken great pride in those accomplishments. But that pride came with an asterisk. I didn’t achieve any of them. They were accomplishments only realized through great teamwork. In the case of my shuttle missions, the team counted in the thousands. Astronauts say, We get into space by standing on the shoulders of others. It’s no exaggeration. We do it on the shoulders of thousands of others.

But in my missions to summit a mountain, success or failure rests entirely on me. In that regard, it is a great metaphor for all life goals. If I make it to a summit, I’m the sole owner of that accomplishment. I don’t share it with anybody. And if I don’t make it due to circumstances within my control, I’m the owner of that result, too. I find that accountability an endorphin rush of the highest order.

But by far, the biggest payback that comes with backpacking is the incomparable beauty and contemplative solitude of the wilderness.

I recall one climb in which I departed my camp at midnight to better the odds of reaching a summit before the thunderstorms started. About 3am I stopped for a drink and turned off my headlamp to look at the night sky. Even the view from a space shuttle couldn’t compete with what I witnessed. There was no structure to compromise the view, no cockpit lighting to interfere, no aurora or gegenschein glow to spoil the utter blackness. I was in a bowl of mountains crowned with a bowl of stars…stars so thick their absence at the horizon emphatically revealed the surrounding peaks as saw-toothed shadows.

And it was vacuum silent. Not a sound. No animal or bird call. No sough of wind. No distant rush of a high-flying jet. Nothing. At that moment, to have uttered a single human word would have been a mortal sin against Nature.

From my pre-hike map study, I knew the trail passed directly above a lake and I turned to find it. What I saw was so rare I was transfixed. The still water of the lake served as a perfect mirror to the view above. The same glitter of stars filled the lake. I was struck with a powerful vertigo, as if I was looking through a hole in the earth and seeing the other side of the celestial sphere. As I stared, a whisper of a ripple moved through the water, probably made by the swish of a fish’s tail or insect-skimming night bird. The mirrored surface undulated, as if infinity had been disturbed by some distant stellar convulsion.

On another occasion Mother Nature’s light show came in the form of a nighttime storm savaging a mountain peak. The blue-white fire of the continuous lightning was accompanied by booming peals of thunder which cascaded ever downward in timbre until finally fading in deep bass breaths. If there was fairness in the Academy Awards, Nature would win best movie and best original soundtrack every time.

On another trip my auditory entertainment came from a pack of coyotes. My campsite was on the rim of a canyon above the Rio Grande…though I could have been camped on an alien planet lightyears away, for there wasn’t a mark of humanity visible in any direction. Around a small fire I watched the full Moon rise above the Sangre de Cristo mountains. In the deepening twilight a pack of coyotes were stirred into their primal lament of yipping and howling. As their hymn echoed eerily from the canyon floor, it drew me into mediation on the timelessness of Nature. Our stone-age forbearers had watched the same Moon rise above the same mountains and heard the same hunting song from the forebearers of these same animals. It was a moment that recalled these beautiful words from 1930’s aviatrix Beryl Markham’s memoir, West with the Night,

“You could expect many things of God at night when the campfire burned before the tents. You could look through and beyond the veils of scarlet and see shadows of the world as God first made it and hear the voices of the beasts He put there. It was a world as old as Time, but as new as Creation’s hour had left it.”

No stair-stepper could take me to Creation’s hour, but a wilderness campfire did.

And I can’t forget the payback of the unique opportunities that come with wilderness solitude, one of which I enjoyed while descending from a climb. At 12,500 ft I stopped at a lake, stripped from my clothes and jumped in. The shock of the snow-melt cold was simultaneously painful and exhilarating…and neutered me for the rest of the day. But after several days on the trail, it felt glorious to dive under the surface and wipe the grime and sweat from my body. I could only endure the cold for a few minutes and swam back to a granite beach where I pulled myself onto the sun-heated rock and laid in the solar warmth like a lazy otter. You can’t do that in the gym…not without putting your membership at risk. But Nature does not judge. She has no dress code. As far as she was concerned, I was just another of her animals. So, I fully enjoyed the rare experience of outdoor nakedness. Nineteenth century American poet and essayist Walt Whitman described the moment in his writings: “Never before did I get so close to Nature; never before did she come so close to me…Nature was naked, and I was also.” Translation: Don’t knock naked in the wilderness until you’ve tried it!

In summary, my ‘thing’ to fool myself into believing I’m not 74 years old, regardless of what the calendar says, has huge downsides. But the payback of the wilderness is incalculable. Its beauty and solitude cannot be found anywhere else in our civilized lives. In a sentence, a journey into the cathedral of the wild, is to fully touch the face of God…or the face of Nature or God’s Nature. Choose whatever you wish to believe.

I’m proud to say, I have led my wife and all of my children into that cathedral and witnessed their joy at the experience.

They (and some of their children) have all stood on 14,000 ft peaks and been awed by 100-mile horizons. All of them have had their spirits refreshed by the sight of a wilderness thunderstorm and a wilderness night sky. That legacy is the ultimate payback.

Well, one other payback does come to mind…the opportunity to smugly refuse a millennial’s offer of a bus seat. I don’t need your damned seat! I’m not old! I’m a backpacker!

Carpe diem.

by Astronaut Richard ‘Mike’ Mullane, Copyright 2019 by Richard Mike Mullane, all rights reserved. Author of Riding Rockets, The outrageous tales of a space shuttle astronaut. Autographed copies of Riding Rockets can be ordered from the Online Store on this website. Photos are from author’s personal family archives, except the space shuttle launch photo, which is a NASA public domain photo.