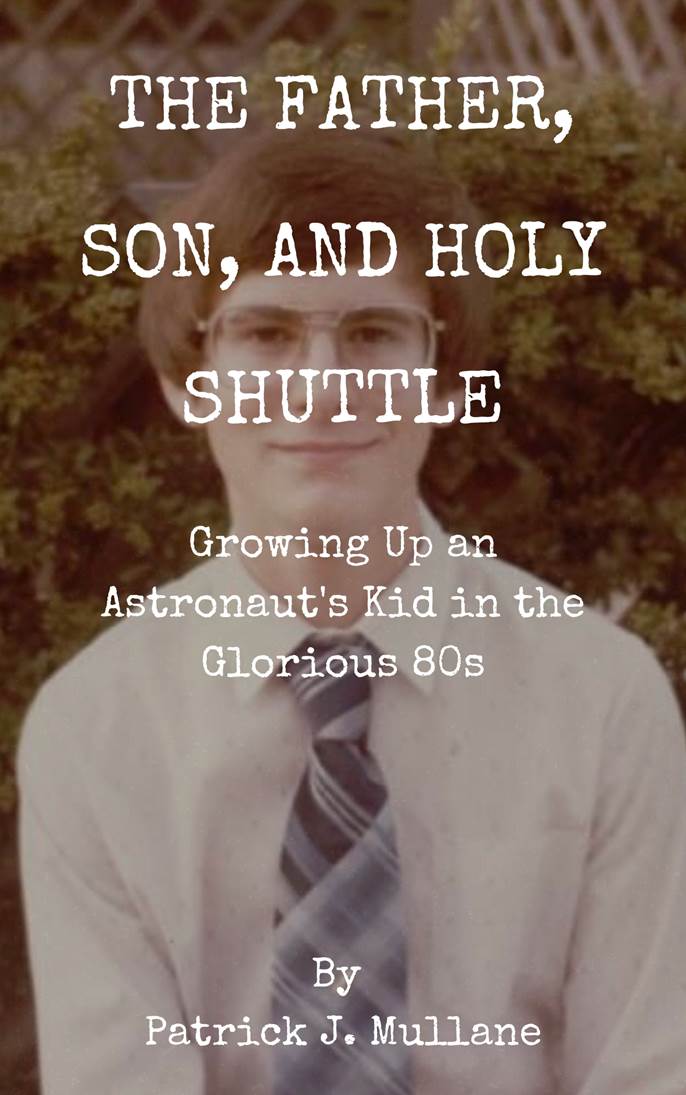

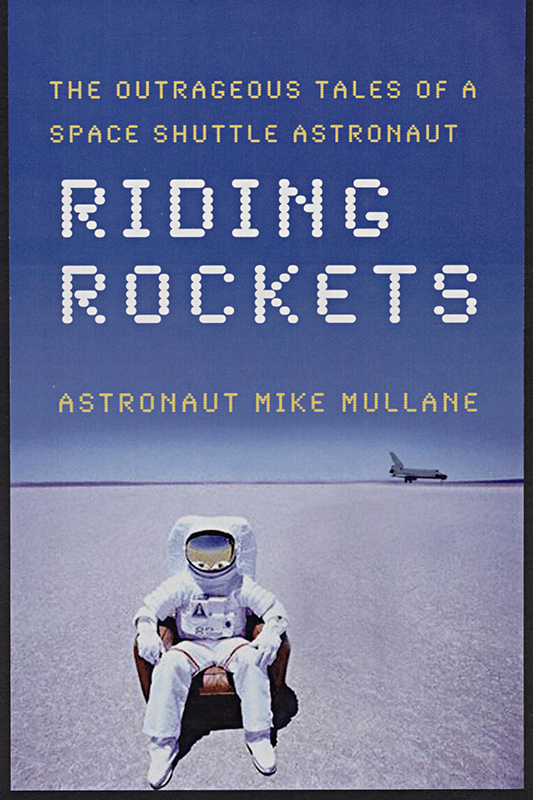

My Road to Vietnam – Early Childhood, by Astronaut Richard ‘Mike’ Mullane, Copyright 2018 by Richard Mike Mullane, all rights reserved. Author of Riding Rockets, The outrageous tales of a space shuttle astronaut. Autographed copies of Riding Rockets can be ordered from the Online Store on this website.

Some photos in this blog are obviously from my personal family archives and to which I hold the copyright. I make no copyright claim for any of the other photos. I took these from the internet and it’s extremely difficult to determine the original copyright for many of the photos posted in cyberspace. But, if anybody sees a photo to which they can claim copyright, I’m more than happy to delete it from the blog or add that copyright. You can contact me through my website: www.MikeMullane.com

My Road to Vietnam – Early Childhood

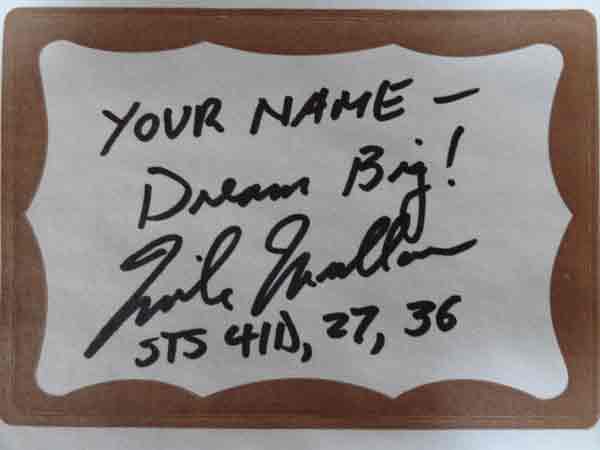

“You missed Korea. But here’s hoping you make Vietnam.”

That’s the only dedication I have in my 1963 high school senior yearbook. While it sounds viciously meanspirited, it was not intended as such. It was penned by a friend of mine, James McGrath. We ran in the same circle of uber-geeks. At our level of immaturity his ill-wish was intended and taken as satirical humor.

But I can’t imagine the source of Jim’s Vietnam reference. At the time he inked it, fewer than 150 American advisors had been KIA in Vietnam. The conflict was a third-page news story. The headlines of that month were on topics far from SE Asia. NASA was in the news with the successful conclusion of its one-man Mercury Program; the civil rights movement was heating up; the Cold War situation in Europe was always on the front pages. So why the Vietnam reference in Jim’s dedication? I never got to ask him. With diplomas in hand we scattered into the rest of our lives. But six years later Jim’s wish that I ‘make it to Vietnam’ was fulfilled and, ironically, his words proved self-prophetic. He ended up serving in the US Navy aboard small gun boats that patrolled the rivers and canals around Saigon. It was dangerous duty and he saw combat action.

For me, January 12, 2019 marks the 50th Anniversary of that moment…the moment I stepped off a military charter flight and onto the tarmac of Tan Son Nhut Air Base, Saigon, Republic of Vietnam. I was at war.

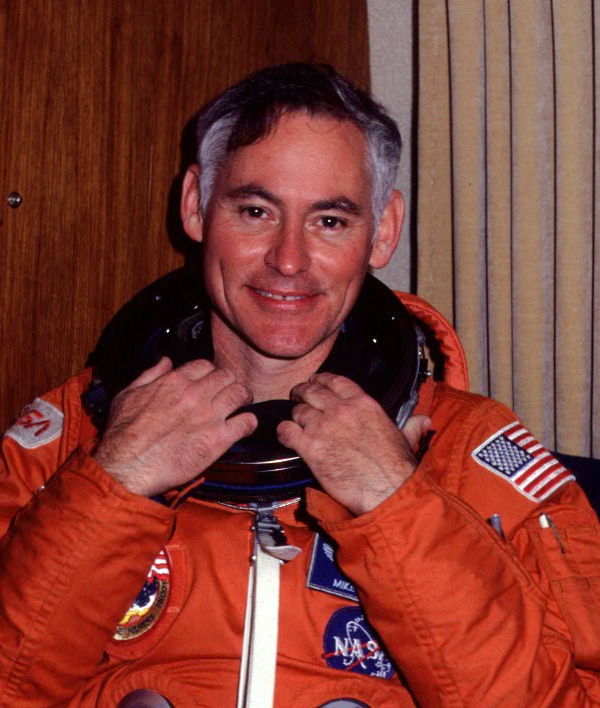

How did I get to that moment? As some of you might know from my memoir, Riding Rockets, or from previous blogs, the short story is this: I was born into a military family; went to West Point; took a commission in the USAF; trained as a back-seater in the RF-4C (the reconnaissance version of the F-4 Phantom fighter); and went to Vietnam in January 1969. But with that anniversary looming, I thought I would document forces in my early youth, some very subtle, that played a part in putting me in that conflict.

(For long-time readers, please forgive some overlap from prior blogs in these next two paragraphs. I’ve put them here as ‘catch-up’ for first time readers.)

I was born two weeks after WWII concluded but my early memories are of all things associated with that conflict. My dad filled my imagination with stories of his war service as a flight engineer/top-gunner in a B-17 squadron stationed in the Pacific. Though he had enlisted in the Army Air Corps before Pearl Harbor, he was not deployed overseas until the final nine months of the conflict. By then, the B-29 Superfortress had taken the air war to Japan, so dad’s squadron saw no offensive bombing action. Instead, their missions involved enemy island reconnaissance, resupply of island bases, and something akin to what we referred to in Vietnam as Crown, a C-130 airborne command post to oversee the rescue of crews bailing out from battle-damaged aircraft.

My father’s squadron of B-17s (6th Emergency Rescue Squadron) were modified to carry a large wooden life boat, packed with survival supplies that could be parachuted to stranded crewmen. Included with that drop were maps marked with the aircraft navigator’s estimate of position and a compass heading the boat occupants should steer for rescue by the nearest friendly forces. The aircraft radio operator would also send location data to American naval vessels in the hope they could pick up the crews.

While my dad didn’t fly into the teeth of Japanese homeland resistance, he remains heroic in my mind. Given the number of men lost due to aircraft malfunctions, bad weather and the immense challenge of flying over the vastness of the Pacific with only the most primitive of navigation aids and weather prediction, I hold every airman from that conflict in the greatest esteem.

After the war, my dad remained in the newly formed Air Force continuing to fly, this time aboard large, four-engine transports. (For the aircraft geeks out there, he crewed C-124 Globemater IIs and C-97 Stratofreighters.)

On some occasions he managed to get my older brother and me into the cockpit of one of these hangered monsters and let us sit in the pilots’ seats and touch the controls. Immediately, that space would be filled with our childish sound effects of machine gun fire and exploding bombs. We coated the inside windscreen with the spittle generated by those effects, no doubt to the great annoyance of the next crew to fly the plane.

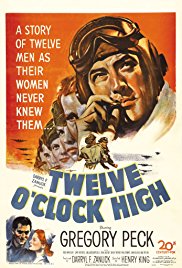

Obviously, my dad was the Jovian gravity that tugged me onto a trajectory toward a military career, one that would ultimately land me in Vietnam. But, as I mentioned earlier, there were other forces in my young life fueling my passion to serve. One of these was the abundance of 1950s Hollywood movies glorifying America’s actions in WWII. In countless Saturday matinees I would sit in an airbase cinema and watch an Air Force-produced, patriotic-themed ‘short’, as a preamble to the main feature. The National Anthem served as the sound track for a film depicting the awesomeness of American airpower. B-36 Peacekeeper bombers droned imperiously, painting the sky in thick contrails. F-86 Sabre Jets swooped low to strafe and unleash canisters of napalm. F-89 Scorpions unleashed fiery torrents of rockets from wing-tip pods. GI Joe parachutists flowed from C-124 troop carriers in seemingly endless ribbons of silk. The final cords of music faded as a formation of new, jet-powered B-47 SAC bombers filled the screen. The message was unmistakable: air power had the preeminent role in national defense. If the Air Force had positioned a recruiter in the lobby, I would have put my 8-year-old signature on a ten-year postdated enlistment form. I wanted to be in those jets, dropping bombs on America’s enemies.

The propaganda finished, Hollywood took its turn on the silver screen. For the next ninety minutes two-hundred popcorn-eating, Coca-Cola-swilling kids sat enthralled as Marines charged into the teeth of chattering Japanese machine guns or hurled grenades into pillbox slits or roasted the cave-dwelling enemy with flame throwers. We would watch American fighters tangle with the enemy’s planes and dive bombers brave flak to drop their lethal loads on Japanese troops and ships. We would cheer en masse as torpedoes swooshed from American submarines and exploded against the sides of Japanese ships.

I learned some very important lessons in those darkened halls, the majority of which would be proved wrong as I navigated deeper into adulthood: that soldiers who revealed photos of their wife or girlfriend were always killed; similarly, soldiers that didn’t have real names, but instead were known as Tex or Broadway, would not survive the last reel; that wounds to cinema heroes were always in the shoulder (fueling my belief that particular part of the human anatomy was nothing other than nerveless, boneless, bloodless, infection resistant, indestructible flesh); that when cinema heroes must die, they always did so after a monologue of inspiration to the remaining men and with their eyes closed; that women were weak and teary and waited faithfully at home; and, most importantly, I learned that America was the greatest country on the planet and always fought on the side of right and justice. And America always triumphed.

It will come as no surprise that I carried what I saw in the theater to my child-play. My brother and our gang of friends would kick open ant hills and legions of the insects were suddenly and unwillingly transformed into the same Japanese soldiers we had just seen in the bomb sights of our cinema heroes. The poor creatures would die under a rain of stone and dirt-clod ‘bombs’ hurled from our juvenile fists. A sidearm, low-angle release of gravel would substitute for strafing cannon fire and send the ants scurrying in confusion…and into more exposed targets for our rocks and clods. (If it turns out hell is run by ants, I’m in very big trouble.)

Only the sound of the Good Humor man would interrupt our aerial extermination. While the ants were left to care for their dead and wounded, I slapped down a buffalo head nickel for an ice-cold root-beer popsicle…best popsicle ever. Of course, while eating that treat, I imagined myself in a Pacific airbase canvas tent conducting a post-mission debrief with the squadron commander. Along with the rest of the pilots we lamented the loss of Ace on our last mission. The poor guy’s nickname had doomed him. And in this mind’s-eye debrief, I wasn’t eating a popsicle. Rather, I was drinking what my cinema heroes always drank after a hellish mission…the doc’s whiskey, whatever that was.

After sucking the final sweetness off our popsicle sticks, the gang would share a pack of candy cigarettes. With one of the red-tipped delights between my lips I was the perfect mimic of Hollywood’s version of a fighter pilot…at least in my mind, I was.

Next came the piéce de résistance. I would reach into my filthy jeans and extract a folded sheet of Bazooka bubblegum and shove it into my mouth. I chewed acres of the stuff just to collect the airplane trading cards that were hidden in the packaging. (I had zero interest in the baseball cards that also came in gum packaging.) The aircraft artwork on the cards was transcendental, the Mona Lisa of my kid-dom. I would stare at the weaponry displayed: gun turrets, protruding cannon barrels, wing-mounted bombs and rockets. When the card was of a WWII fighter I would visualize cannon fire shredding the meatball insignia on the wing of a Japanese fighter. Flipping the card over, I would read the performance table for the aircraft…its top speed and ceiling; its range and bomb load. I memorized the stats for every plane I collected and would recite them to anybody who would listen…and even to those who wouldn’t. I thought there was something seriously wrong with the boys who did the same thing with the batting averages and ERAs shown on the backs of the baseball cards. It was wasted brain space to memorize that crap, I thought.

Among my circle of playmates, the Air Force’s new YB-49 flying wing was the ultimate treasure of trading cards. Try as I might though, I was never able to chew my way into acquisition. When I ultimately held that Holy Grail, won by another cavity-riddled, bubblegum addict, I did so with all the awe and reverence I saw priests give to a consecrated communion wafer.

Candy cigarette manufacturers and the Bazooka gum company weren’t the only corporate entities that turned my eyes skyward. The Revell model company also played an out-sized role in transforming me into an airborne warrior. Over the years, I built countless of their plastic aircraft replicas. In fact, the company’s financial bedrock was the silver of my Mercury-head dimes. As a devoted consumer, I lived my childhood in a perpetual haze of toxic glue and paint fumes. My dad’s garage work bench was stratified in epochs of the dried residue of those chemicals. And every kid-airplane-modeler of my era will know of what I speak, when I say there is no more sacred, more joyful experience, than that climactic moment when the aircraft insignia decals were delicately slid from their wetted paper backings and onto the plastic. Then, the transformation was complete. The P-38 plastic model on my desk disappeared. In the Twilight Zone in my mind, it had been taken back in time and transformed into a real P-38 roaring through Pacific skies and I was in the cockpit seeing a Japanese fighter in the gunsight, my thumb on the gun-switch. Just like in those matinees, another enemy plane went down in flames.

Ultimately, those models would hang by thumb-tacked fishing line from my bedroom ceiling, but first they were thrown into combat. I would set up my GI Joe plastic army figures as ersatz Japanese troops. Holding my newly minted fighter in my hand and with fingers clutching the plastic model bombs that came with the kit, I would swoop low over the enemy army and release my lethal ordnance on them. They fell by the score.

As breakages from multiple handlings took a toll on my models, they were re-purposed into another war prop. I would smuggle one from my bedroom, along with a tube of glue, while another member of the gang would sneak a box of matches from their home. In an indifferent, purposeless stroll (kid stealth-mode), we would spy an adult-free area in a back alley and bolt for it. There, we would smear the model with the flammable glue, light it on fire and hurl it skyward into a final role as a shot-down Japanese fighter.

On other occasions a model’s final flight was assisted with more sophisticated pyrotechnics…fireworks. The moment any of those explosives appeared in the midst of the pack, I would dart to my room for a castoff model. After a brief discussion on how best to tape the firecracker or cherry bomb for maximum destructive power, and the selection of the fuse-lighter, the craft would be catapulted into its last fight, courtesy of a shovel. A four-kid harmony of machinegun mimicking followed its arc. None of us were seeing a toy model tumbling through the air. It was a Japanese Zero with a P-38 Lightning on its tail. With the sharp crack of detonation, the enemy was dismembered in mid-air. America wins again.

In 1953, my dad was given orders to report to Hickman AFB, Oahu, Hawaii and the family embarked on a Navy transport ship out of San Francisco. Trapped parents were desperate to find relief from a seven-day confinement with their kids and the US Navy obliged. We were herded into a darkened room where non-stop Disney cartoons played. In what I can only assume was a Navy attempt to indoctrinate us, as the Air Force did in their base theater showings, there was a too-generous serving of Popeye the Sailor cartoons. I came to loathe those features…as did the rest of the audience. We howled and booed in derision when the toot-toot of the tugboat sounded. Fewer kids could be coaxed into another day of watching the spinach-muscled, tattooed, pipe-smoking sailor and his anorexic, flat-chested girlfriend, Olive Oyl. Finally, the Navy got smart and loaded the projector with a WWII-themed movie. Once again, all was right in my Universe. I watched the same movie multiple times a day, over multiple days and, to me, each showing remained fresh and thrilling. On the few breaks I would take, I would be at the ship’s rail imaging I was aboard a destroyer depth-charging an enemy sub.

If ever there was a place in 1953 that could take me back to WWII, it was Hawaii. Not even Hollywood’s magic could compare. The island’s military bases still bore scars from the Pearl Harbor attack. The concrete water tower near my elementary school was pock-marked with shrapnel damage. The battleship Arizona, with its eleven-hundred entombed men, was a constant reminder of that Day of Infamy. And, as a major cross-roads for America’s post-war defense forces, the Hawaiian skies were constantly filled with Air Force and Navy aircraft. When huge Navy seaplanes were scheduled to land or depart from Pearl Harbor, my dad would load the family into the car and drive us to watch the novelty.![]()

But the most fun for my brothers and me was Waikiki Beach. At the time the island tourist industry was nascent and that now-famous beach was largely a deserted virgin. From its sand we would collect pristine shells colored in pink and flamingo swirls and dive into the surf to break off chunks of living coral (there was no such thing as environmental awareness in the early ‘50s). We were Crusoes, as brown as natives from the hours we spent in the sun and surf.

But even the siren call of the sea could not keep us long. We would hear a louder call from nearby Fort DeRussy. Originally built to defend Hawaii from a battleship-led fleet attack, it had been equipped with huge cannons. But, as history so often reveals, it was designed by Generals and Admirals preparing to fight the last war and when the opening attack of a new war finally came, it was from the air. Not a shot was fired from the fort and, after hostilities ceased, it was abandoned.

In all of kid-dom there is no more volatile catalyst to the imagination than the words ‘fort’ and ‘abandoned’. While the heaviest DeRussy artillery had been removed from their revetments, there was more than enough remaining weaponry to serve as props in our war-play. We spent hours crawling over the crumbling concrete and shinnying ourselves up the rusting lengths of log-sized gun barrels. The right-of-first-occupation of the metal gunner’s seats always resulted in a shoving and pushing match. The winner would wrap his fingers around the multiple wheels used for aiming the device and look through the concentric circles of the iron sights. Along with this play was the never-ending, kid-sounds of gunfire and explosions and the aerosol mist of saliva that came with it. Shouts of, “I got it!”, denoting another Japanese Zero flaming to earth, echoed among the walls. Elsewhere in America the war might have been over, but it continued to rage at Fort DeRussy, Hawaii, fought by Tim, Mike and Pat Mullane.

In 1955, the tragedy of polio ended my dad’s service. Left a paraplegic, he was discharged and a family migration to Albuquerque, New Mexico followed. It had a VA Hospital, which my dad would need in his rehabilitation.

As I matured (in age, not necessarily in behavior), my dreams of military service grew more vivid. Even the music I listened to beat a martial note. The bedroom I shared with two brothers had a turntable and a stack of LP records, none of which featured teen pop-hits. Instead of listening to Elvis’ All Shook Up (the number one teen hit in 1957), we spun out operatic and classical hits like Ride of the Valkyries and the William Tell Overture. It was the music of my mom and dad and I loved it. I was particularly infatuated with Tchaikovsky’s 1812 Overture as it contained musical cannon fire. (In case you’re wondering, I didn’t date a lot in my teen years…as in, never.) Later, as Russia assumed its place as America’s arch-enemy, I felt betrayed to learn that Tchaikovsky’s work celebrated Russia’s victory over the French. But, at age 12, ignorance was bliss and many a night I lay in bed oblivious to the fact I was hearing Russian musical cannons blasting the La Marseillaise and Napoleon’s army to pieces.

The same bedroom also featured two, wall-mounted war-themed lithographs. One was a depiction of Confederate Major General George Pickett’s unsuccessful attempt to turn the tide of defeat at Gettysburg. The composition contained everything my imagination needed to place me on the Union side…the side of right; the side of justice, the side of America. Frozen in paint was a chaotic scrum of gray and blue-clad men, muskets belching yellow flames, officers holding pistols at the ready, swords and bayonets thrusting. And there I am, maintaining my grip on the Union Colors, pushing the enemy back with nothing but a defiant scowl. I could smell the gunpowder.

The other lithographic art was of a squadron of B-24 Liberator bombers skimming low over the burning oil tanks of Nazi-occupied Ploesti, Romania. The perspective was that of an observer in the rear of a leading plane looking aft into a maelstrom of flak and fire. I’m a pilot in one of the planes and, just like my matinee heroes, I have my hands locked on the controls shouting encouragement into the intercom to rally my frightened crew. Again, I was on the side of right, the side of America.

A final nudge toward military service came from an eight-year journey through Albuquerque’s private Catholic schools. At various grade levels, I experienced that religion’s obsession with worms, lice, sex and communism. It was the latter obsession that threw gasoline on my fire to embrace the combat arms.

(I’ll post a future blog on Catholicism’s obsession with lice and sex.)

As I previously mentioned, I was born in the bloody shadow of WWII. But even as the confetti from the New York City victory parades was falling, the seeds of a new war were germinating…a Cold War. Communist Russia was intent on world domination. All doubts as to that ended in 1956 when Russian Premiere Nikita Khrushchev issued his most direct statement of intent, “Whether you like it or not, history is on our side. We will bury you!” And the Russians were more than happy to lend their support to any dictator willing to speed that burial along, including Kim Il Sung of North Korea (the grandfather of the current ruler). His invasion of South Korea in 1950 was supported by the Soviet Union. My dad cursed the Russians for their hand in the butchery of American boys that followed. I learned at my father’s knee that you can’t hate the commies enough.

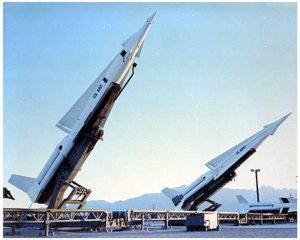

The Russian threat wasn’t contained to foreign lands. An existential nuclear threat existed a continent away…in the bomb bays of Soviet bombers (and later, on the tips of their missiles). Baby-boomers grew up with a loaded, cocked, nuclear gun aimed at our heads. We learned the symbol for radiation fallout shelters. They were ubiquitous on entrances to building basements. There were commercial bomb shelter manufacturers. One of my playmates’ dad installed one under his back yard. (We loved playing in it.) Public servants with grave expressions appeared in TV announcements instructing the population on how to prepare for and survive a nuclear attack. Free government booklets on home preparation could be ordered. Schools had periodic ‘duck-and-cover’ exercises in which we practiced ducking under our desks and covering our heads with our arms as protection against a hydrogen-bomb blast. (Even we kids had doubts as to the effectiveness of such a drill.) Air raid sirens were periodically tested and major cities were protected with Nike Hercules and Bomarc anti-aircraft missile batteries. (My roommate from West Point was stationed at a Nike Hercules battery near Sausalito, CA.)

There were commercial bomb shelter manufacturers. One of my playmates’ dad installed one under his back yard. (We loved playing in it.) Public servants with grave expressions appeared in TV announcements instructing the population on how to prepare for and survive a nuclear attack. Free government booklets on home preparation could be ordered. Schools had periodic ‘duck-and-cover’ exercises in which we practiced ducking under our desks and covering our heads with our arms as protection against a hydrogen-bomb blast. (Even we kids had doubts as to the effectiveness of such a drill.) Air raid sirens were periodically tested and major cities were protected with Nike Hercules and Bomarc anti-aircraft missile batteries. (My roommate from West Point was stationed at a Nike Hercules battery near Sausalito, CA.)

Supersonic fighters and B-58 Hustler bombers sonic-boomed the countryside in their training and nobody complained. Newsreels showed SAC alert crews roused from their meals and bunks by the sound of klaxons and running from their quarters to board nuclear-armed B-52 bombers. In fifteen minutes, they were airborne. SAC also advertised its most powerful deterrent… airborne alert missions. These consisted of ever-repeating formations of nuke-loaded B-52s and their KC-135 tanker support aircraft, maintaining an airborne 24-7-365-year-after-year retaliatory force circling near the Russian arctic border awaiting the President’s orders to attack.

It was the Soviet menace that President John F. Kennedy was addressing in this sentence from his 1961 inaugural address:

“Let every nation know, whether it wishes us well or ill, that we shall pay any price, bear any burden, meet any hardship, support any friend, oppose any foe, in order to assure the survival and the success of liberty.”

A translation: “Any action on your part, Mr. Khrushchev, to bury America and we will leave Russia a sterile wasteland for ten-thousand years.”

As if my multi-year daily immersion in all of this wasn’t enough to cement Russia as a spawn of Satan, the Catholic church took up the baton with a vengeance. And they had good reason to do so. Communism had no room for Christianity, or any religion for that matter. Karl Marx, one of the key fathers of Communism, made that clear when he said, “Religion is the opiate of the masses.” In the Communist manifesto there was room for only one supreme leader: the State. Or, more specifically, the First Secretary of the Communist Party. Allegiance to anybody else, temporal or spiritual, was a crime against the State.

While I seriously doubt the Vatican gave a rat’s furry posterior about the Protestant branch of Christianity being exterminated, or all other religions erased from the planet, they certainly took the threat of their own eradication with deadly seriousness. And, as we all know, the key to defeating any enemy, is to first know that enemy. Toward that end, Catholic children were subjected to a lengthy anti-communist brainwashing.

We first learned Russia was a wretchedly poor, third-world country. Multiple bar-graphs in our textbooks illustrated the economic disparity between the USA and the USSR. Small symbols of telephones, cars, TVs and other consumer goods, each representing one million units of that item, were stacked in columns. Where there might be 50 stacked symbols for a particular item in a USA column (50 million of those items), there would be a laughable half-symbol representing the same item’s abundance in the USSR.

We got the message. Russia would have been a forgotten backwater, except for the fact it had The Bomb….lots of them. And their nuclear-club membership was only attributable to their theft of our nuclear secrets. The most infamous of these Red spies were Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, a husband and wife team who passed secret nuclear documents to their Soviet masters. In 1953, when I was eight years old, I recall my mom stopping the car to listen to a broadcaster announce the electric-chair execution of the couple. When I asked my mom what was happening, she replied, “Some bad people did a bad thing to America.” Even as a child, I could sense her primal fear for her children.

By my high school senior year, I was proficient in the dialectic and language of Marxism: the class struggle between the proletariat and bourgeoise; socialism; capitalism; revolution; and the ultimate triumph of communism.

In the final exam of these studies we were confronted with our instructor (a Priest) assuming the role of a member of the Party, intent on converting us to the dark-side. Religion was nothing more than a fairy tale, he insisted. Faith in a God-figure blinded us to the glory of the State. A workers’ paradise would elevate us and help us achieve our true potential. Catholicism was an opiate fed to us by a bourgeois Pope…a Pope who sat in the gilded luxury of the Vatican counting his riches. It was treasure picked from the pockets of the proletariat through the lie that tithing was required to get into a non-existent heaven. Our faux Commissar hammered home the primary message: there is no Jesus, no God, no afterlife. But a real, temporal utopia could be created in America, just as existed in Russia. All it took was for workers to unite under the red banner of Communism. In that system everybody shared equally in the abundance created by the worker’s collective efforts. All those bar-charts were Catholic and capitalists lies. Russia was an earthly Garden of Eden of peace, wealth, happiness and joy. Turn your back on your religion with its priests and Pope. Come to enlightenment. Come to communism!

We eagerly raised our hands, anxious to be called upon to counter every statement with Catholic theology. After a strong resistance of repeating the indisputable certainties of communism, our Party advocate began to hesitate and stumble, as if the error of his atheism was slowly dawning. The Communist Manifesto was no match for the Baltimore Catechism. Our Comrade Father finally caved. He saw the error of his ways. We passed the test.

It was only later I would realize the irony of using the brain-washing of one belief system to defend against the brain-washing of another. In a way, communism and Catholicism shared the same playbook, i.e., feed the message to the kids as early as possible and continue to do so until the synapses in their brains were irrevocably hard-wired with it. Speed that process along with an abundance of fear…fear of the Gulag (Russia) and fear of Hell’s fire (Catholicism). The priests and nuns proved the equal of any KGB minion. Catholic kids stepped out of high school as anti-communist cyborgs. The diploma we held carried the unwritten message…to kill commies was to do God’s work. And God’s work was waiting for us in Vietnam, for the enemy in that far away land had been labeled Communist.

So, I was destined to end up in Vietnam. I was destined by my dad’s fierce patriotism and by Hollywood’s glorification of the WWII American fighting man. I was destined by Bazooka Gum Company’s airplane trading cards and by the Revell Model Company. I was destined by my war play at Fort DeRussy and by the Civil War and WWII artwork in my bedroom. I was destined by Mr. Khrushchev’s bellicose threats and duck-and-cover drills. And I was destined by Catholicism’s anti-communist obsession.

But war was still six years away for me. First, I had to become an American fighting man. A month after graduation I was winging my way to West Point.

…to be continued.

My Road to Vietnam – Early Childhood, by Astronaut Richard ‘Mike’ Mullane, Copyright 2018 by Richard Mike Mullane, all rights reserved. Author of Riding Rockets, The outrageous tales of a space shuttle astronaut. Autographed copies of Riding Rockets can be ordered from the Online Store on this website.

To my readers: I would like to recommend the Blog that my astronaut classmate and great friend, Dr. Rhea Seddon, publishes. She provides another perspective on the astronaut experience which many readers of my blog would enjoy. Here’s the link:http://astronautrheaseddon.com/latest-updates/