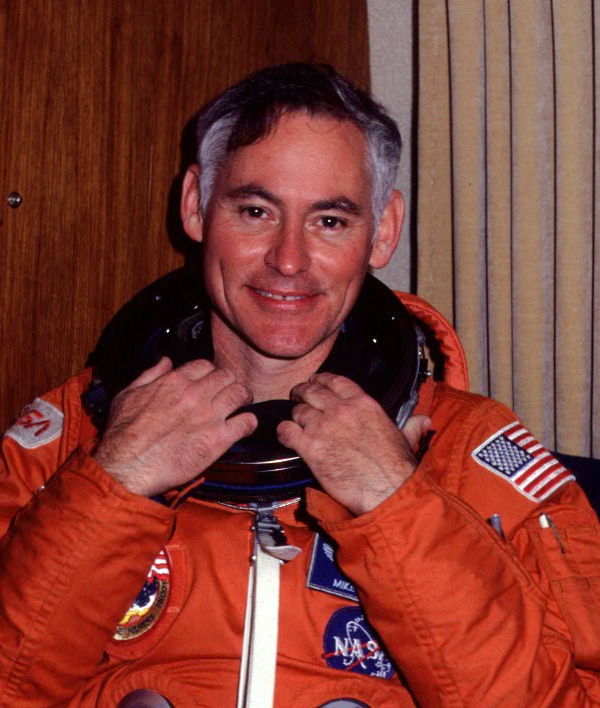

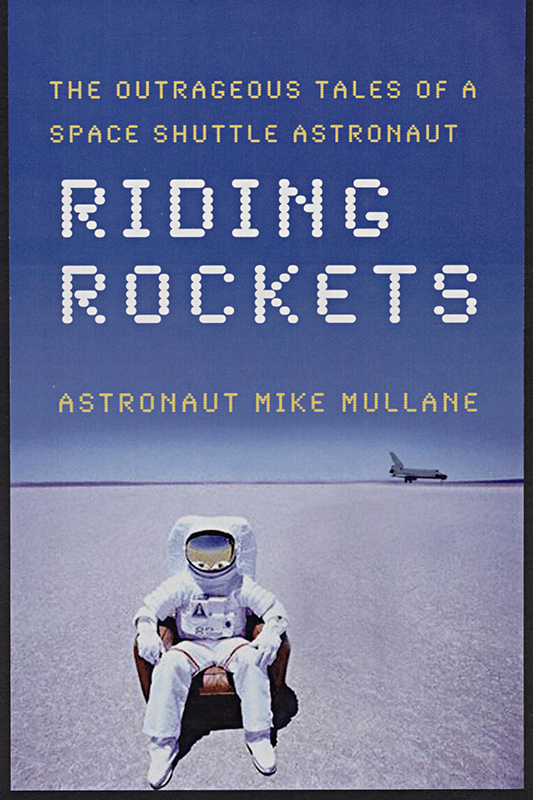

Copyright 2018 by Richard Mike Mullane, all rights reserved. Author of Riding Rockets, The outrageous tales of a space shuttle astronaut.

- “…NASA’s drive to achieve a launch schedule of 24-flights per year created pressure throughout the agency that directly contributed to unsafe launch operations.”…House Committee on the Challenger Disaster

Like my earlier post, this entry is also on the topic of the loss of the space shuttle, Challenger. Tomorrow, January 28th, marks the 32nd anniversary of that horrific day. Below, you will find an article my adult daughter, Laura, wrote several years ago. I’m posting it here (and intend to do so on every anniversary of the disaster) because of its unique perspective. Laura eloquently captures how the shadow of Challenger darkened her childhood. It is a cautionary story for everybody who leads teams involved in hazardous operations. Place safety above all else. The House Committee finding on the tragedy (above) says it all. Challenger was a schedule-driven disaster, a theme in many workplace fatalities…all of which cast their own long tragic shadows.

The Long Shadow of Challenger

Originally posted January 28, 2011, for the 25th anniversary of the Challenger tragedy. By Laura Mullane. Copyright 2011 by Laura Mullane

I was home sick. Strep throat, I think. I had been home for several days. It was ninth grade, and I remember being anxious about all the school I’d missed—the tests I would have to make up, the gossip I would be unaware of, what the boy I had a crush on was doing every day. My dad was on TDY (military speak for a business trip). My mom was at the boutique where she worked part-time. I was lying in bed, reading the novel The Quartzite Trip, and listening to the radio. The DJ came on after a song and said in an impossibly upbeat voice, “There’s news about the space shuttle exploding! Not sure what’s going on. We’ll get back to you with more details.” And it cut to commercial.

I couldn’t believe it. I ran downstairs to our family room and turned on the TV, and there it was: the space shuttle Challenger blooming. That’s what it looked like. The rocket’s singular plume of smoke blossoming like a flower.  Which mission was this? Yes, the teacher’s mission. How could I forget? It had been on the news incessantly. Christa McAuliffe’s celebrity-weary smile flickering across our TV screens every night. I didn’t know her. She didn’t matter to me. Who mattered were the rest…whose parents were these?

Which mission was this? Yes, the teacher’s mission. How could I forget? It had been on the news incessantly. Christa McAuliffe’s celebrity-weary smile flickering across our TV screens every night. I didn’t know her. She didn’t matter to me. Who mattered were the rest…whose parents were these?

Alison’s father. Of course. I’d seen her in the hallway a few days before she left for Florida. I didn’t really know her. She was in my class and we had friends in common, but that was it. But I had seen in her face that same anxious anticipation I’d felt a year and half earlier, before I made the same trip to Cape Canaveral to see my father’s first launch. There was Janelle, too. She and I had played together when we were younger, when we first moved to the neighborhood—a dozen or so astronauts all in the space of a few blocks of each other. And there was Dick Scobee. His kids were older, but we had all lived together at Edwards Air Force Base in California, when our fathers were in test pilot school. Judy Resnik. She had flown with my dad on his first mission. They had been close. They’d go jogging together and she would come to our house for dinner.  She seemed unreal to me, unlike any other women I’d known growing up. She was single and childless, for starters. And an astronaut. Most of the women of my childhood were housewives or secretaries or dental hygienists. She was young and beautiful. I didn’t know what to make of her.

She seemed unreal to me, unlike any other women I’d known growing up. She was single and childless, for starters. And an astronaut. Most of the women of my childhood were housewives or secretaries or dental hygienists. She was young and beautiful. I didn’t know what to make of her.

The Challenger was exploding again and again across the screen. I called my mom at work. “Mom,” I said, sobs already choking off my words. “What happened?”

“I don’t know.”

“Are they going to be okay?” I thought they would be. They had to be, right? Surely the engineers had anticipated something like this and given them a way to escape. They would be floating in a raft in the ocean somewhere.

My mom took a deep breath. “No, honey, I don’t think so. I think they’ve died.”

I couldn’t breathe. I hung up the phone and cried. I imagined the families standing on the roof of the Launch Control Center, watching this.  During my father’s first launch attempt, the engines had cut off at T-4 seconds to lift off. A swirl of smoke encircled the base of the rocket. A rumbling boom echoed across the water. We had thought it was an explosion. A few moments of terror before the relief of learning it wasn’t. The families that stood on the roof of the LCC now would never get that relief. Instead each moment would only be worse than the last.

During my father’s first launch attempt, the engines had cut off at T-4 seconds to lift off. A swirl of smoke encircled the base of the rocket. A rumbling boom echoed across the water. We had thought it was an explosion. A few moments of terror before the relief of learning it wasn’t. The families that stood on the roof of the LCC now would never get that relief. Instead each moment would only be worse than the last.

My dad would fly home that afternoon. My brother and sister would come home from school early. They were seniors and had been called to the office by the principal and told the news before the announcement had been made over the PA system—when the rest of the students would learn that their neighbors and friends’ parents and parents’ coworkers had been killed. So much grief. How could we hold it all?

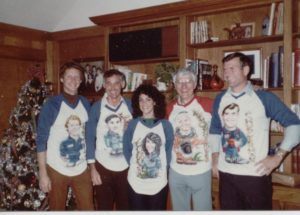

I don’t remember much beyond that. Just pixilated images. My dad coming home. He and my mom standing in the kitchen, holding one another. My mom sobbing. Tears rimming my dad’s eyes. The phone ringing constantly—mostly press calls my father refused to take. So many people at our house. My dad’s astronaut friends, many of whom he’d known long before he became an astronaut, and their wives and children congregating in our kitchen and living room. The perpetual hum of the TV in the background.

But mostly, I remember Alison. St. Bernadette’s Catholic Church, where my and other astronaut families were parishioners, held a special memorial service. Alison was there. It was the first time I’d seen her since the tragedy, except on TV. I kept my distance. It was easy. The church was packed and I could get lost in the crowd. But I couldn’t take my eyes off of her—her face swollen with the weight of grief, her shoulders rounded as if trying to protect her heart from a fatal blow. But it was too late.

I adored my father. His infectious laugh. His stupid jokes that he told over and over again. The way he always said “no sweat” when things looked bad—after rapids had overturned our raft and we were tumbling through the water without life jackets toward boulders hungry for skulls; our car sliding off the road in a snowstorm; a long-horned bull chasing us across an open field. Life with my father seemed bigger than other lives, and I was always trying to harness it. I would never be able to live without that. I couldn’t fathom it.

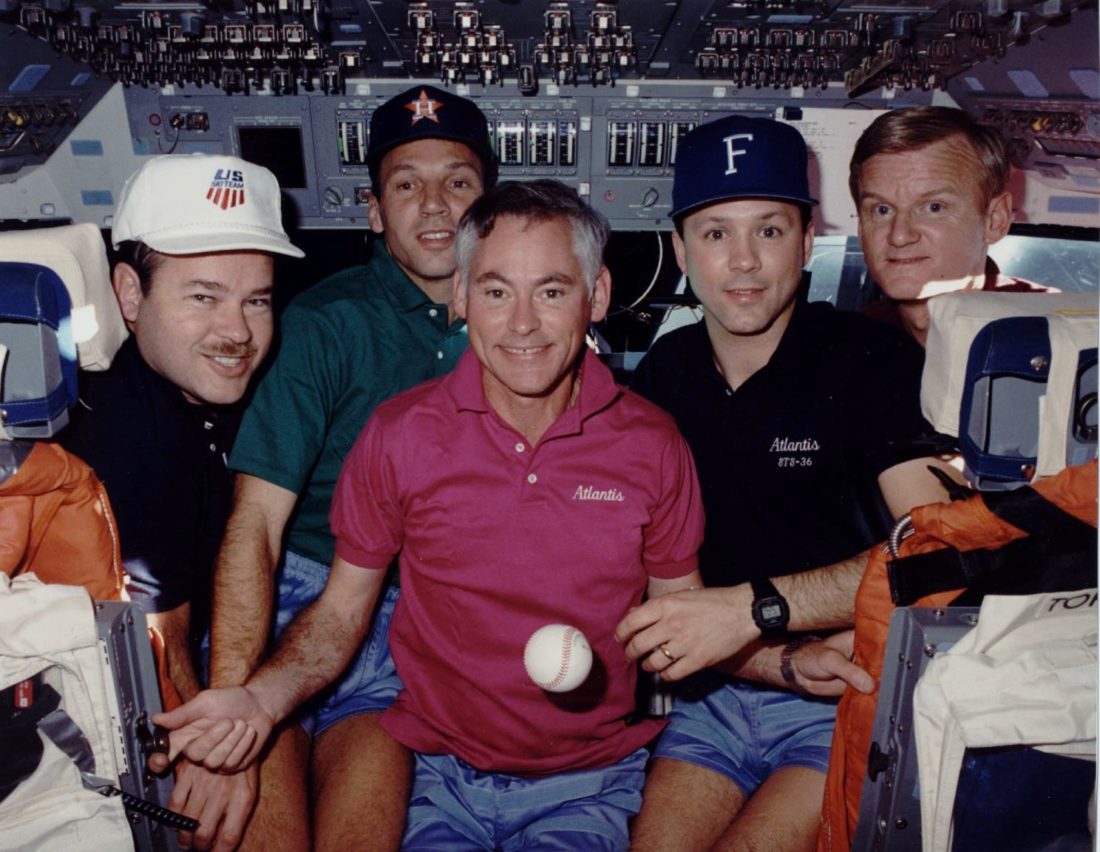

And I didn’t have to. My father survived his first shuttle mission before Challenger and the two that followed. He took the exact same risks as Alison’s father, and he returned. It seemed impossibly unfair. For the next four years, Alison and I would pass each other in the hallways. We would go to the same parties. We were in the same classes. But I never really talked to her. I couldn’t bear the guilt.

The worst was during the senior musical, which Alison and I were in together. My dad’s second launch was just a couple weeks before the show, so I was gone for a week of rehearsals. When I got back into town, I went straight to the theater, where the cast stood on the stage, practicing. I walked into the auditorium and several of my friends ran up to me. “Laura!” “Oh my God, was it amazing?” “Was it fun?” “Were you scared?” Out of the corner of my eye I could see Alison sitting on the stage, watching. I wanted to yell at everyone to shut up. To just pretend I’d been here all along. Like I’d never left. Like I wasn’t even here now. Pretend I don’t exist. Pretend I’ve disappeared.

The worst was during the senior musical, which Alison and I were in together. My dad’s second launch was just a couple weeks before the show, so I was gone for a week of rehearsals. When I got back into town, I went straight to the theater, where the cast stood on the stage, practicing. I walked into the auditorium and several of my friends ran up to me. “Laura!” “Oh my God, was it amazing?” “Was it fun?” “Were you scared?” Out of the corner of my eye I could see Alison sitting on the stage, watching. I wanted to yell at everyone to shut up. To just pretend I’d been here all along. Like I’d never left. Like I wasn’t even here now. Pretend I don’t exist. Pretend I’ve disappeared.

My dad’s mission was over by the show’s first curtain. He came to watch the play and some of the cast made a sign for him that said something like: “Some dads really go the distance to get to opening night!” I wanted to rip it up. Everything associated with my father’s career reminded me that my dad was alive and Alison’s wasn’t. My father would see me graduate from high school and, later college. He would see me get married. He would hold his grandchildren. Hers wouldn’t.

I never talked to Alison about any of this, until a few months ago, when I had the idea to write an article about it and emailed her, asking if I could interview her. Over a phone call, she told me about those awful days and I told her how guilty I’d always felt, my voice cracking with tears as I did. Her voice cracked, too. “Thank you so much for telling me that,” she said.

I always see that day 25 years ago as a seminal moment in my life. The day that everything changed. Of course, everything changes all the time. My life has been filled with countless moments that have forever altered the way I view the world. But there was something about that day that made it so much bigger than the rest. Part of it was because it was a national tragedy…a public mourning for something that felt so personal. But it was more than that. It was the first time in my life that I realized that life—and death—are random. That there are things we can’t control. But mostly I learned that although grief wraps itself around us and threatens to squeeze the life from our lungs, it never opens its jaws. It doesn’t consume us. Alison grew up. She went to college and got married and had kids. So did the other astronauts’ children. And if my father had been one of those killed on Challenger, so would have I. We exist even in those moments when we least want to. Life pulls us forward in spite of ourselves.

The Long Shadow of Challenger

Originally posted January 28, 2011, for the 25th anniversary of the Challenger tragedy. By Laura Mullane. Copyright 2011 by Laura Mullane

Copyright 2018 by Richard Mike Mullane, all rights reserved. Author of Riding Rockets, The outrageous tales of a space shuttle astronaut.