CHALLENGER POINT MEMORIAL

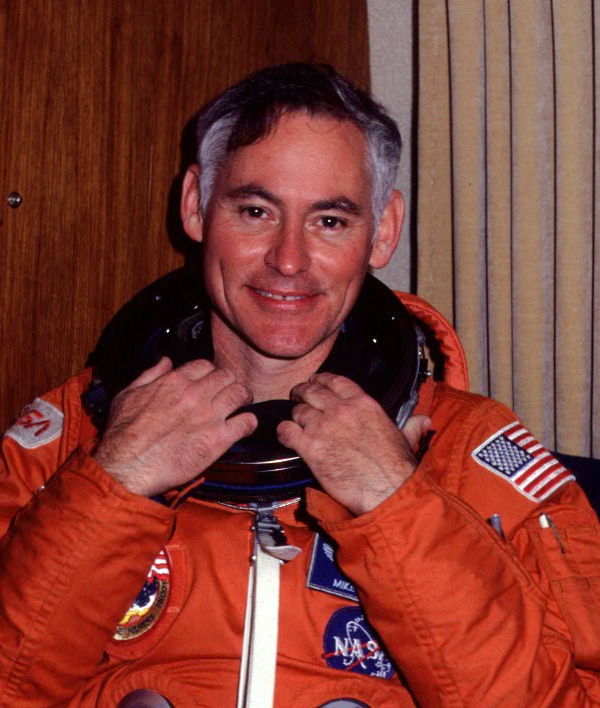

By Astronaut Richard ‘Mike’ Mullane

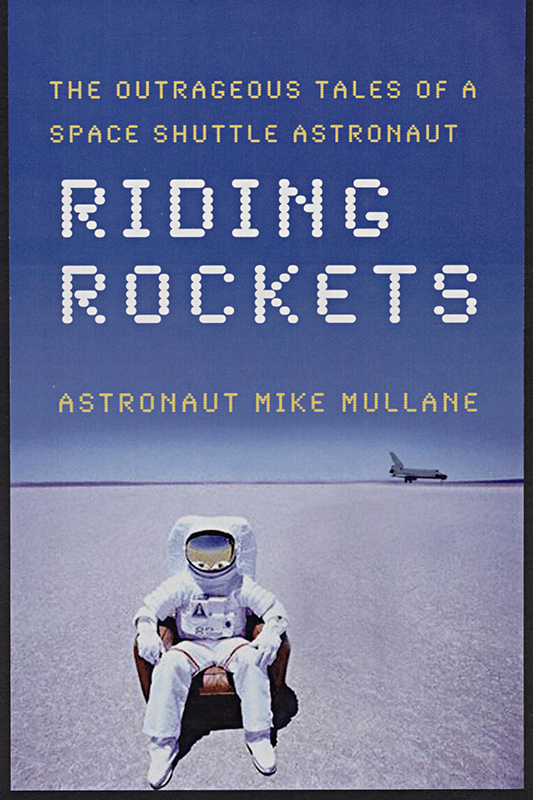

Copyright 2018 by Richard Mike Mullane, all rights reserved. Author of Riding Rockets, The outrageous tales of a space shuttle astronaut. Autographed copies of Riding Rockets can be ordered from the Online store on this website.

It is certainly the most remote memorial to the space shuttle Challenger crew ever constructed. I doubt more than several hundred people have visited it in the three decades since it was established. To see it requires a one-way climb of six miles and 5400 vertical feet of elevation, ending on a Colorado peak over 14,000 feet above sea level. A casual space enthusiast will never see it. In fact, it took me three attempts to reach it, my previous efforts having been thwarted by deep snow on one occasion and a vicious thunderstorm on another. Success finally came on October 3, 2008, when my brother and I dropped our packs and slumped in exhaustion at the base of the memorial.

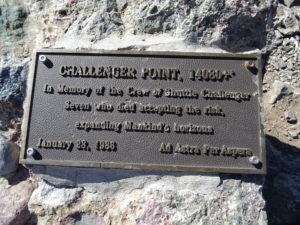

It is elegantly simple…a brass plaque measuring six by twelve inches and bolted to a wedge of rock forming the very peak of Challenger Point. Two sentences of upraised text captures the meaning of exploration and the sacrifice that often accompanies it:

In Memory of the Crew of the Shuttle Challenger. Seven who died accepting the risk, expanding Mankind’s horizons.

A footer gives the date of the disaster, January 28, 1986, and the Latin phrase, Ad Astra Per Aspera. (Through hardships to the stars.)

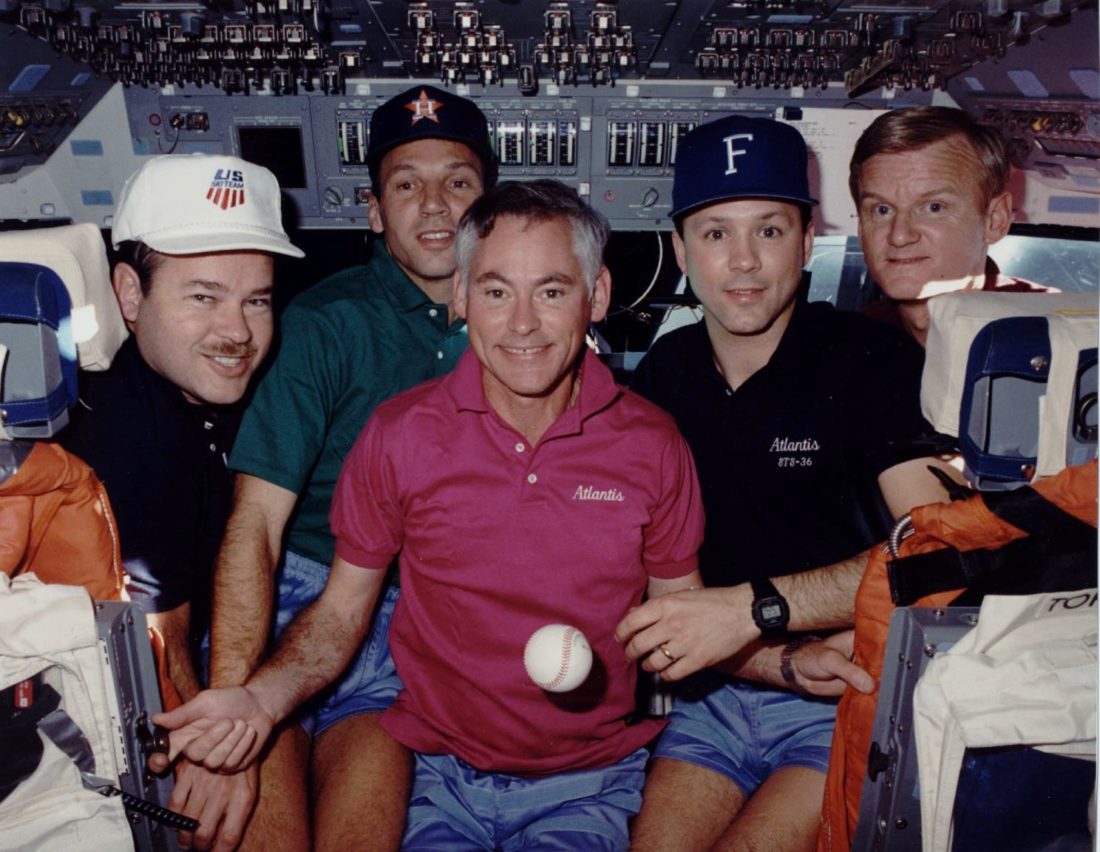

Whoever did this had gone to some expense and significant physical labor. Who and why, were obvious questions. No astronaut had placed it. Of that, I was certain. I had been immersed in the tragedy of Challenger. You can read more about that in my memoir, Riding Rockets, but the salient facts are that four of my astronaut classmates were killed on Challenger, including Judy Resnik. Judy and I flew together on our rookie mission in 1984 aboard the maiden flight of the shuttle Discovery. Had any astronaut placed a memorial on Colorado mountain, I would have known it.

Several years after my summit, my computer screensaver flashed a photo I had taken of the plaque. It was enough to energize me to pursue the story behind its placement. Former astronaut Scott Parazynski seemed like a good place to start. In 2003, he led a mission to place a plaque memorializing the space shuttle Columbia crew on a Colorado peak.

Several years after my summit, my computer screensaver flashed a photo I had taken of the plaque. It was enough to energize me to pursue the story behind its placement. Former astronaut Scott Parazynski seemed like a good place to start. In 2003, he led a mission to place a plaque memorializing the space shuttle Columbia crew on a Colorado peak.

Scott quickly answered my email. The summit plaque was installed in 1987 by a space enthusiast, Alan Silverstein. Included with this information was Alan’s email address. Alan and I were soon linked in cyberspace and set up a telecom.

My immediate impression of Alan during that phone call was that he was a closet astronaut…a ‘detail’ man in the extreme. He possessed an eidetic memory of his work to place the plaque and, even if his memory had been faulty, he had archived a wealth of data on the effort, including several blogs. The only problem I encountered in documenting the details was that Alan delivered them at terabyte baud rate. I have been accused of speaking fast but, compared to Alan, I was the DMV sloth in the movie Zootopia.

After earning a degree in software engineering in 1977 from Caltech, Alan took a job with Hewlett Packard in Ft. Collins, Colorado and spent most of his working career at that site. After a few other forays in the corporate world, he declared victory and retired at the early age of fifty-seven.

Like many others, Alan watched the Challenger tragedy live on TV and was deeply traumatized by it. It might have ended there, with Alan being among the multitude wishing, fruitlessly, they could channel their grief into something constructive.

Enter Dennis Williams, a Colorado Springs Ford Microelectronics engineer. Like Alan, he was one of that multitude, but saw something he could do or, at least, try to do…get a Colorado peak named to memorialize the Challenger crew. Dennis was a climber and familiar with an unnamed 14,000 ft point on the west shoulder of Kit Carson Peak, a dominant feature in the Sangre de Christo mountain range, just to the east of the small Colorado town of Crestone. Why not have that unnamed terrain designated Challenger Point, he thought. Seems simple enough, but nobody can just name a peak. There’s a bureaucracy for that; specifically, the US Geological Survey’s (USGS) Board on Geographic Names (BGN). Dennis wrote that agency with his naming suggestion and also solicited the help of other climbers via an early web climber-community bulletin board. Alan, himself a climbing enthusiast, saw a newspaper article about the naming effort and wrote his own letter of support to the USGS for the peak-naming.

The wheels of the bureaucracy began their grind toward a decision and, with remarkable speed for any government agency, Challenger Point was officially placed on the map on April 9, 1987.

It was with the peak naming that Alan began to seriously consider the idea of placing a plaque on the summit, as a visible and lasting memorial to the Challenger crew’s sacrifice. It was going to take a lot of time, some money and considerable physical labor to complete such a task. What would motivate somebody to this effort?

Though ten years my junior, Alan was young enough to experience the thrill of the latter part of the space race. At the very impressionable age of thirteen, he watched Neil Armstrong step onto the lunar surface.  As it did for me, that race to the moon sparked a consuming interest in Alan for all things related to space. “I still have some boxes of space memorabilia which contain some astronaut-autographed lithos that I requested from NASA.” I collected the same material in my youth. Included in his story was the fact he interned at the famed Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) for a summer in his university days.

As it did for me, that race to the moon sparked a consuming interest in Alan for all things related to space. “I still have some boxes of space memorabilia which contain some astronaut-autographed lithos that I requested from NASA.” I collected the same material in my youth. Included in his story was the fact he interned at the famed Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) for a summer in his university days.

Alan’s space bonafides were ironclad, but being moonstruck doesn’t put a plaque on the wind-swept, oxygen-deprived peak I climbed. It takes an enormous physical effort. I’ve summited forty of the fourteeners (the climber slang for the 14,000 foot peaks in Colorado). The climb to Challenger Point is officially listed as a ‘Difficult Class 2’ on a climbing scale of Class 1 (easiest) to Class 5 (death, for those who don’t know what they are doing). After my own summit, I would replace the descriptor Difficult with Brutal. The fact I made the climb at age sixty-three might color my opinion on the degree of pain involved, but I passed a number of twenty-somethings who had given up on their attempts.

Alan, it turned out, was more than qualified to take on a Difficult Class-2 climb. As a younger man, he booked the Colorado climbers’ grand-slam of summitting all fifty-eight of the State’s fourteeners. “I’ve been to the top of some of them multiple times, and I’ve even slept the night on ten of them.” Some people have too much energy, I thought.

But a couple obstacles to placing something permanent on the peak loomed. One such obstacle resided within Alan himself. Alan was a rock-hugger and worried about violating Mother Nature’s pristine mountain-top virginity with something as obscene as a man-made object. “I’ve been a rock-hound and amateur geologist all my life. It bothered me to think about bolting something to a summit rock.” And he worried other members of the climbing community would find the idea equally offensive. With this in mind, he contacted the Colorado Mountain Club, of which he was a member, seeking consensus on the plaque plan, “They endorsed the proposal but declined to arrange or join in any sort of ceremony.” Their endorsement was enough for Alan.

Another obstacle to the plaque plan was that the newly named Challenger Point was on private property, specifically it was part of the Baca Land Grant. At this point, a lot of mission-focused people (myself included) would have adopted the attitude of, better to ask for forgiveness, than for permission. (Who is going to demand that a plaque memorializing the Challenger crew be removed from a rock?) But Alan, as I said earlier, was a dot-the-i’s-and-cross-the-t’s detail man. He contacted the owners by phone and explained his plan. They expressed little interest in and no objections to a plaque on the peak.

He felt the path was now clear to address the other details of the mission: how big of a plaque, what to say on it, how to place it, what tools would be needed, etc. He enlisted the help of another climber, Jim Baer, a Ball Aerospace employee, and over the phone they nailed down the size and wording. Alan estimated the cost of the plaque, gas and other expenses would be would be approximately $240 or about $500 in current year dollars.

I asked if he requested help from NASA for some press visibility for his mission. “I did. But the public affairs office was disinterested.” I can well imagine they were. The Rogers Commission report on the Challenger disaster was submitted to the President just a year earlier. Within its pages was the revelation that the tragedy was totally avoidable. The NASA/Contractor team failed to properly address a known problem with the booster rocket. The press feeding-frenzy to place blame for that bureaucratic failure was still raging a year later, when Alan made his call. I’m sure the harried official at the other end of the line was up to his neck in snapping press-sharks and had no time for some guy with a bizarre plan to place a plaque on a mountain peak.

Alan was more successful with some third-tier newspapers and magazines in his efforts to generate some press buzz for the plaque mission. And, a Fort Collins school, Shepardson Elementary School, sponsored a fund raiser which netted $100. A local trophy business was helpful in getting the plaque delivered before the short climbing season in the high Rockies ended.

And, of course, Alan had his own engineering self-sufficiency to rely upon, “In the weeks before the trip I busily over prepared. I made a long list of tools and supplies we might need on the summit, bought and tested a variety of concrete compounds, drew up a plan for how we might attach the plaque, gathered everything together and weighed the parts…Being uncertain of what to expect on the summit, I was prepared for a variety of alternatives.”

Throughout his preparations, Alan kept the climbing community involved. He extended an invitation to Dennis Williams to join in the climb, but he declined. Jim Baer would join with his friend, Barbara Roach. Barbara was another Colorado grand-slammer mountaineer. Ted Manahan with HP in Colorado Springs signed on. His wife Chuchang and eight-month-old son Clifton would accompany them to the Willow Lake base camp. Joe Hunter, another Colorado Springs HP engineer, wrote that he would be part of the expedition.

The group would total seven, including a baby. Alan was glad for their help. The additional weight of the tools, plaque, anchors and cement would add thirty-five pounds to the heavy load normally required for a multi-night climb into the high country. Dividing that pain would be a godsend. Alan set the target date for the climb as the weekend of July 18, 1987. Besides the fact that day was in the middle of National Space Week, it was also late enough in the season that most of last winter’s snow would have melted.

On Friday, July 17th, the group, minus Joe Hunter, who was to meet them the following day at Willow Lake, rendezvoused at a campsite off a dirt road east of the small (and very ‘new age’) town of Crestone. Remarkably, until that moment, none of them had ever met. Their common cause to establish a permanent monument to the Challenger crew was the magnet which pulled them together.

In the morning, they apportioned the added weight among themselves, completed their packing and drove the two miles to the trailhead. At 9:30am they stepped out, destination Willow Lake, 2800 vertical feet and a little over four miles away. If there’s any part of the climb that can be considered just plain difficult, it’s this portion. The trail is well cut and the grade has been lessened by a seemingly endless series of switchbacks.

Luckily, the weather was fair. While July makes it much less likely that snow will be a show-stopper, the summer monsoons are usually in full swing at that time of year and the thunderstorms they contain pose a lethal lightning danger, particularly above the timberline. And they would be spending a lot of time above that line.

Since they planned an overnight stay at Willow Lake, their pace was leisurely. Alan and the others traded turns carrying little Clifton. Alan never argued the logic of bringing a baby along for the hike. Since mom and dad were present, Clifton was no risk to mission success. And most climbers have a laissez faire attitude about fellow climbers. Whatever works for them is fine, even bringing an infant. I’ve seen it before. On one of my fourteener climbs I encountered a modern-day Sacagawea in the form of a young woman, alone on the trail at the twelve-thousand-foot level, breast feeding her infant. Seriously, where do people get this energy?

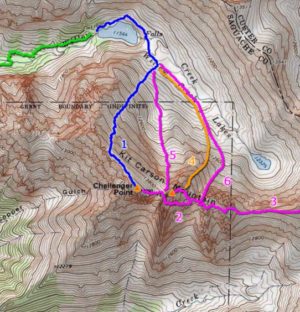

About an hour into the hike, the group crested a ridge and, below them, the narrow valley drained by Willow Creek came into view. For the next mile, their path paralleled the north side of that valley. In the near-distance the major terrain to be ascended on this first day of the expedition was visible…a virtually sheer wall rising a thousand feet to the higher reaches of the valley where Willow Lake was located. Only those switchbacks made that terrain climbable. In the far distance, Kit Carson Peak, at 14,165 feet, ruled the view. Challenger Point, forming the highest terrain on the south side of the upper valley, was not yet visible.

About two hours from the trailhead, they reached the towering wall separating the upper and lower valleys and began with the necessary, but aggravatingly wearisome switchbacks. Another two hours of climbing put them on the floor of the upper valley and the grade significantly lessened. From there, it was an easy half-mile hike to Willow Lake, their base camp. The seventh member of the expedition, Joe Hunter, hiking by headlamp, reached the camp after dark.

Describing Willow Lake is like describing a sunrise seen from Earth-orbit. English language superlatives don’t do either scene justice. Gouged from rock by an ancient glacier, Willow Lake, at 11,600 feet above sea level, is roughly oval shaped, about two-tenths of a mile long and about half that distance at its widest. It sits at the lowest end of the upper Willow Creek valley. Three sides of steep, alpine terrain direct snow melt into the bottom of that narrow valley to form the creek which ultimately enters the lake via a two-hundred-foot-high waterfall at its east end. At the west end, a natural spillway drains the lake and the water continues a stair-stepping plunge for four thousand feet, before it finally exits into the San Luis Valley. To stand on the cliff edge of the waterfall and look west, down the length of the lake, and see no obstruction to the view except a horizon sixty-miles away, is to believe God wanted an infinity pool and put it on Earth in the form of Willow Lake. There could not be a more beautiful base-camp location.

At 4:45am on Sunday, July 19th, Alan and Joe awoke to a hint of dawn. The weather remained good…cold, clear and a brisk southwest wind. After a quick breakfast, the two men hefted packs containing the essentials to start the placement of the plaque and left the others. Jim, Ted and Barbara would follow later. Chuchang and baby Clifton would remain at the campsite.

Alan and Joe quickly reached the waterfall cliff, which also marked the timberline, and turned to face their objective…Challenger Point a mere 2400 vertical feet in elevation above them. Beside the exceptional steepness of the naked slope….an average of fifty percent grade…the terrain was a conglomerate of slippery tundra grass on the lower reaches, yielding into a tilted moonscape of rotten rock in the higher reaches. There were no switch-backs to lessen the grade and no single trail to follow. Past climbers had twisted and turned their way through the rocks leaving a spaghetti of multiple pathways. Rock cairns, marking what prior climbers considered the least-worst pathway, had multiplied to the point being useless. Firm footing was rare. Much of the upper climb was through gravel. One step up and a half-step slide backwards. Repeat. This was the part of the climb that earned the mountain the Difficult qualifier, to its Class 2 label.

At 8:05am, after a two-and-one-half hour fight with gravity, Alan and Joe stood upon the newly named Challenger Point. They p aused a moment to take in the Godly view. To the south was a tempest of sand…the waves of Colorado’s Great Sand Dunes; to the northeast the hulk of Kit Carson Peak loomed.

aused a moment to take in the Godly view. To the south was a tempest of sand…the waves of Colorado’s Great Sand Dunes; to the northeast the hulk of Kit Carson Peak loomed.

They located a summit registry, contained in a piece of PVC, which was placed by a hiker in 1985. The last entry for 1986 was by Dennis Williams, the initiator for the peak naming. To that moment only an additional ten climbers had recorded entries for 1987. That would change in the future, as Alan’s plaque would bring more climbers. But the registry he now read revealed not everybody was a fan of the naming. One entry was a long screed about the foolishness of naming the mountain after Challenger. Others wrote words critical of that diatribe. “Go at Throttle Up!” was one comment.

They began site selection. Ever the engineer, Alan searched for a north-facing location to minimize sun-induced cycles of thermal expansion which could jeopardize the long-term integrity of the plaque’s anchors. In the process of that search Alan was stunned to uncover some human bone chips, ashes and a small brass token with text reading, “Ferncliff Crematory, Hartsdale, NY.” Obviously, there was story here but it would have to wait until he returned home. He made a pencil and paper rubbing of the token to aid future research.

A north-facing location could not be found, so they settled on the next best thing, the northeast-facing slope of the summit boulder itself and began the excruciatingly slow process of chiseling that area into some semblance of flatness. That task was followed by the most difficult part of the placement preparation…using a star chisel and hammer to drill four, two-inch holes for lead anchors. Each hole consumed about forty minutes of labor and several finger injuries.

Reinforcements arrived at 10:00 am in the form of Jim, Ted and Barbara and everybody took a turn with the hole drilling…and finger abuse. Around noon, after four hours of labor, they were ready to set the plaque. Alan described the moment,

“Two people mixed Quikrete, a fast-hardening concrete, while we squeezed silicone cement into the anchor holes, put modelling clay plugs on top, then coated the rock with acrylic bonding compound. We put several of the bone chips on the prepared rock, then we spread the concrete, positioned the plaque and tightened it down, forcing cement out and around the edges. We used three stainless steel and one (longer) steel Allen-head cap screws.”

Matt Damon’s character in the movie, Martian, could have taken a lesson from Alan and his team on how to get things done in an alien environment.

In a very thoughtful gesture, one of the team gathered the extra cement and fixed the crematory token onto a different rock near the previously discovered remains.

After using rags for a final cleaning of the plaque, they were done. The expedition gathered their tools, took some final photos and paused to admire the product of their extraordinary effort, before beginning their descent back to Willow Lake. Alan described the moment in his after-action blog, “Now this was a magic time…quiet, peaceful…the culmination of our hard work gleaming in the sunlight…From here, the horizons were indeed very far away.” He continued, “I hope the plaque lasts for a long time. Long after people…have forgotten how it came to be there.” He concluded with a quote from Philosopher William James, “The greatest use of life is to spend it on something that outlasts it.”

Alan’s wish has, thus far, endured for nearly thirty years. My brother and I made a second summit of Challenger Point in the Fall of 2016, a necessary waypoint on the hike to our objective, Kit Carson Peak. As I stood over the plaque, my memory slipped back to my last conversation with Judy Resnik. The day prior to her death, I called to wish her good luck. “Thanks, Tarzan (my nickname, when we flew together on our rookie mission in 1984). I’ll see you back in Houston.” Of course, we would never meet again. But standing on that peak, on the limb of the earth, looking to the far horizon, I couldn’t help but think the spirit of the crew was present and would always be so. Alan and the others had done a very good thing and I hope, too, it outlasts all of us.

After returning home, Alan reached out to Dr. June Scobee, wife of Dick Scobee, the Commander of the ill-fated mission, “Eventually I received a very nice reply, including a thank you note written on a copy of the map quadrangle showing the peak. So, she, and perhaps the other astronaut’s families, are aware of Challenger Point and the memorial plaque.”

Alan also pursued the story of the human remains. The Ferncliff Crematory was still in business and a call revealed the token number referred to the remains of Mr. Russell Johnson Parker of New York, who died on September 9, 1949 at age 52. He was cremated on September 16th and the ashes were mailed to Walter H. Williams. There was no address available for Mr. Williams.

After hearing Alan’s story, I passed along this information to my sister-in-law, Sue Mullane, for additional research. She is the family’s resident ancestry guru. Employing her skills, she discovered Mr. Parker was a globe-trotting mining engineer born, August 31, 1897 in Olney Springs, Colorado. In the 1910 census, he was in Crestone, Colorado, the town dominated by Challenger Point. It’s easy to imagine that, as a mining engineer, he explored the surrounding peaks, including what would become Challenger Point, and, at some point in his life, made a wish known that his cremated remains be left on that peak. She also learned there were several Walter Williams living in Colorado at the time of Parker’s death. Some of those Williams lived in the Olney Springs area. It could be surmised that Mr. Williams was a very close friend of Mr. Parker, perhaps the two worked together in the mining industry and, Williams himself, made the climb to put the remains on the peak. That will forever remain a mystery. However, I can believe an explorer like Mr. Parker would have liked the idea a portion of his remains would someday be preserved under a plaque memorializing fallen explorers from another age.

Sadly, the Challenger crew would not be the only fallen astronauts to be memorialized in these mountains. As Alan and his crew stood admiring their work, they could not know in sixteen years, the high point of the eastern shoulder of Kit Carson Peak, not more than a mile away, would bear the name Columbia Point and be crowned with a memorial to that space shuttle crew. That is a story best told by astronaut Scott Parazynski.

CHALLENGER POINT MEMORIAL

By Astronaut Richard ‘Mike’ Mullane

Photos are courtesy of Alan Silverstein, NASA and author. Map photo is courtesy of 14ers.com.

Copyright 2018 by Richard Mike Mullane, all rights reserved. Author of Riding Rockets, The outrageous tales of a space shuttle astronaut. Autographed copies of Riding Rockets can be ordered from the Online store on this website.