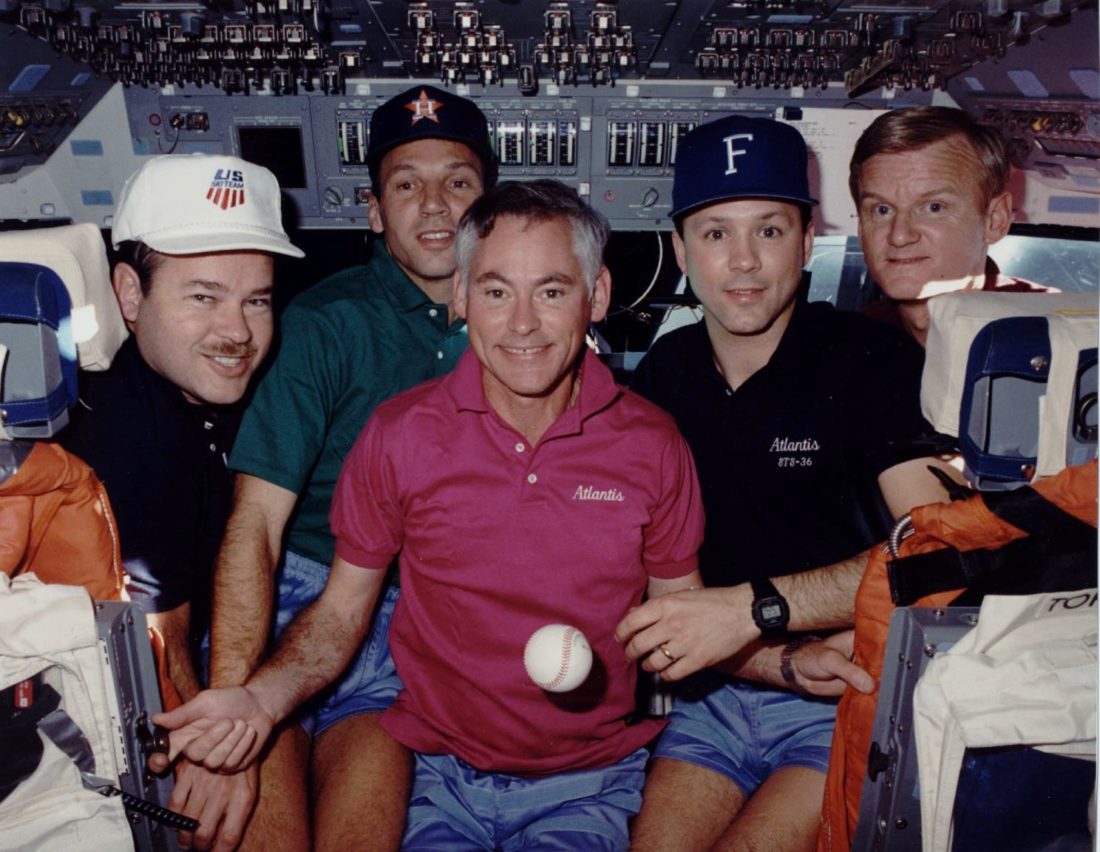

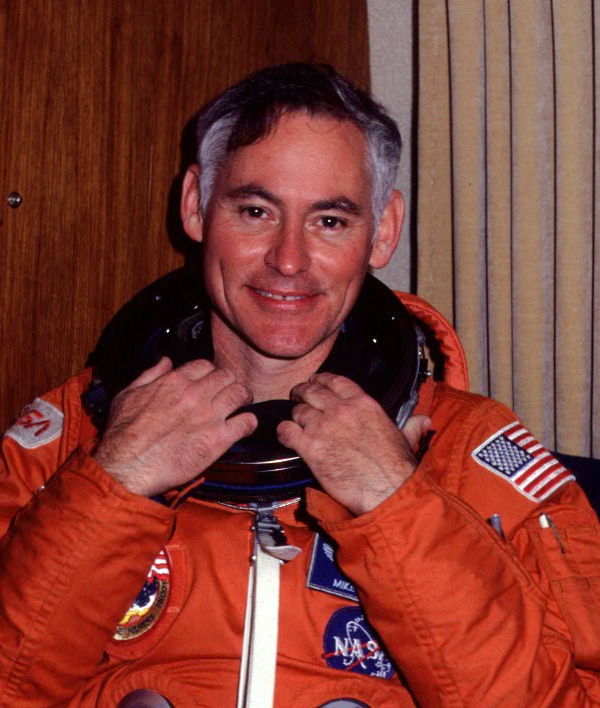

REUNION By Astronaut Richard ‘Mike’ Mullane, Copyright 2018 by Richard Mike Mullane, all rights reserved. Author of Riding Rockets, The outrageous tales of a space shuttle astronaut. Autographed copies of Riding Rockets can be ordered from the Online Store on this website. (Photos which are not the author’s are either public domain or used with the permission of the photographer.)

As a favor to a close friend, Master Sergeant Tim Gagnon of the Air Force Reserves, I was recently at Fort Huachuca Army Post near Sierra Vista, AZ to speak at a Civil Air Patrol Cadet summer camp. My wife, Donna, and I had driven to Tucson a day early to meet for dinner with Tim and his family and a friend of Tim’s, Lt. Col. Martin Meyer and his wife. As a way of saying ‘thanks’ for my volunteer work with the CAP, Tim had a surprise arranged for me the next day and he revealed it at dinner. I would get a tour of the Davis-Monthan Air Force Base aircraft boneyard, led by Lt. Col. Meyer. Martin is head of aircraft testing at the facility.

I was thrilled by Tim’s gift. I had long wanted to visit the boneyard. It’s Mecca for anybody with an interest in aviation. Covering 4500 acres of desert are over 3300 used military aircraft awaiting various dispositions. Some are placed in flyable storage for possible return to service with American or allied forces or conversion to water bombers for wildfire fighting. Others are modified to serve as pilot-less drones. Currently, these drones are pulled from the ranks of F-16 fighters and Martin test-flies them as part of the drone conversion process. (They are flyable by pilots, as well as operable as drones.) In the drone mode these F-16s experience short, second lives as targets in new weapon systems testing. But most of the aircraft in the boneyard are destined for the claws of demolition and the furnace of recycling.

The day of my tour dawned as every day dawns in a Tucson June…sunny, scorching heat and a zero chance of a cloud, much less any rain. Martin drove us in a government van while patiently answering my many questions.

In rank after rank hundreds of Army helicopters were neatly parked with parade-ground precision. There were acres of B-52s, KC-135s and C-130s. F-15s and F-16s were parked in laser-perfect lines. C-5 Galaxies can be counted by the gross.

There were acres of B-52s, KC-135s and C-130s. F-15s and F-16s were parked in laser-perfect lines. C-5 Galaxies can be counted by the gross.  There were Navy sub-hunters, A-6 Intruders and A-4s. F-14s sit silent, when once their kin thundered in the movie Top Gun.

There were Navy sub-hunters, A-6 Intruders and A-4s. F-14s sit silent, when once their kin thundered in the movie Top Gun.

I was most interested in seeing one of the surviving F-4 Phantom aircraft. I had flown in the backseat of the reconnaissance version of the Phantom, the RF-4C, in the Vietnam War in 1969. It would be nice to get a photo next to one of those. But I had little hope for such a photo. The vast majority of F-4 models were of the fighter version, not the reconnaissance version. Moreover, Martin said there were only about a half-dozen F-4s remaining in the boneyard and those were being cut up for recycling daily. We’d be lucky if any F-4s of any model were remaining. Tim and Martin had tempered my expectations. I had no clue it was all an act.

The C-5s couldn’t help but seize the eye and I asked for a stop to pose for a photo…while being watchful for rattlesnakes. The C-5s were the monsters in this aircraft Jurassic park, the largest aircraft ever to enter the USAF inventory. Each was capable of carrying two, sixty-ton Abrams tanks across oceanic distances. Now, they were as grounded as a fossilized Quetzalcoatlus (For those who are dino-illiterate, the Quetzalcoatlus is the largest flying animal ever discovered).

Back in the van we continued to loop through this silent ghost-Air Force, while Martin explained various aspects of the boneyard operations and drone conversion. A sad hulk of an F-111 swing-wing fighter bomber…of the type used in the bombing raid on Libya in 1986…came into view and I asked for another photo stop. I had flown in the right-seat of the F-111 while stationed at Eglin AFB in 1976.

Finishing with my F-111 photos I looked around and noticed a pitifully small covey of F-4s parked nearby. I was just in time. I was looking at the sole survivors of a force of USAF and Navy Phantoms that once numbered in the thousands. I’d be able to get the photo I most wanted.

Approaching the jets, the memory of the very first time I had strapped into a Phantom came rushing over me. I had graduated from navigator training at Mather AFB in Sacramento, CA in the summer of 1968 and ordered to report to Mountain Home, AFB in Idaho for training in the RF-4C.

I would be flying in the back seat of a Mach 2 aircraft. My training quickly produced lifelong memories…the push of nearly 36,000 pounds of combined thrust from the two, J-79 afterburning engines; the squeeze of a 6-g turn; the transonic jump in the airspeed indicator as the speed of sound was exceeded.

As I was posing for a photo next to the first F-4 I came to, Martin pointed out another jet in the group and commented, “You really need to pose next to that one.” His emphasis on that aircraft struck me as odd. He added, “You flew it in Vietnam.” I was utterly confused by the statement. But it caused me to study the jet more closely. Because the boneyard F-4s were cocooned in a spray-on protective plastic, at first glance they all looked the same…fighter versions. Then I noted the ‘chin’ under the nose of this particular jet…a distinctive characteristic of an RF-4C.

It was the window for the forward-looking camera. I was seeing the last RF-4C aircraft in the USAF inventory and only days before it would be destroyed. Martin’s comment now made sense to me. He had been referring to the same model aircraft I had flown in Vietnam. Of course, that would be the one I would want for my photo. But Donna rekindled my confusion. She thrust a piece of paper into my hand. “Here’s a copy of your flight log from Vietnam. You flew this exact plane in Vietnam.” I gaped open-mouthed. What the hell was she talking about? How could she know that? What is going on?

The explanation came, best told by Tim Gagnon in his post on my visit:

“There is a certain relationship that military aircrew have with the airplanes they flew and specifically into combat. This past weekend, I was part of an extraordinary event that lead to the reunion of combat veteran and his airplane. It all started simple enough with a request to have my friend retired Col. Mike Mullane speak at a gathering of Civil Air Patrol Cadets in southern Arizona. Mike and his wife Donna would be making the very long drive from Albuquerque to Sierra Vista for the chat. I figured if they were going to make such a drive, I would fill the weekend with a more expansive visit. The famous aircraft boneyard in Tucson is a cool tour and having access to it would make it even cooler! That is when the idea hit me to see if any of Mike’s RF-4’s were in there. He was a Weapon Systems Officer in Vietnam. I covertly contacted his wife and asked her if any of his original flight logs were still around. They were and we got to work! She photographed all the logbook pages and I started my research. Over the next few weeks, I went through each page and compared the airplane tail numbers to multiple sources. I was hitting a brick wall and was afraid no RF-4’s were left in yard. One tail kept popping up but there was some confusing information so I dug deeper. After finding some promising information, I sent the tail number to a friend who runs flight test at the boneyard (this friend was Lt. Col Martin Meyer). He said things looked good but wanted to confirm and took a drive out to the airplane to confirm. He responded that it was indeed the same airplane!! We found one! There was an issue, she was scheduled for destruction in the coming weeks. He went to his commander and pleaded to give our find a brief stay of execution so we could get Mike and Donna out for his visit. The commander agreed! Now, there are 3300 airplanes currently in the boneyard scattered over nearly 4500 acres. Of those 3300 airplanes, there are only six F-4’s left and of those six, only ONE RF-4. 64-1038…Mike’s RF! Read that again…it was the ONLY RF-4 left in the yard! By the way, he flew in 64-1038 only once…ONCE! A literal needle in a haystack!”

I looked at the records Donna had given me. One particular entry was highlighted. On August 2, 1969 I had flown a three-hour mission in tail number 64-038. Sure enough, faintly visible through the protective paint on the tail of the aircraft in front of me, was the same number: 64-038. I couldn’t believe it. It didn’t seem possible. But Tim continued to reassure me that I had flown in this exact jet nearly a half-century earlier.

I couldn’t believe it. It didn’t seem possible. But Tim continued to reassure me that I had flown in this exact jet nearly a half-century earlier.

When the reality finally took root in my brain, I was overcome with emotion and turned to embrace Tim, Martin and both Donna’s (mine and Tim’s). All had been part of the conspiracy to bring me to this place and this moment. I couldn’t stop saying ‘thank you’. It was an incredible gift and a stellar example of the deep friendships, even love, that is shared among men and women in uniform. To say members of the armed forces are a band of brothers and sisters, is not an exaggeration.

This moment was living proof. Tim, a toddler when I had been in Vietnam, had started the ball rolling and brought in Martin for help. I had never met Martin. When an eleventh-hour reprieve was needed to save 038 from destruction, Martin brought in his Commander for help. I had never met Martin’s Commander. Band of brothers/sisters indeed!

Tim’s Donna, documented the moment in multiple photos. (Many of those are included with this post…a shout out to Donna Gagnon!) Tim climbed onto the wing and helped me up…not an easy task since I was still in recovery from spinal disk surgery a couple months earlier. Donna positioned me on the wing, such that the tail number would be visible, yielding my favorite photo from the morning.

Finally, it was time to leave. I said a silent goodbye to the machine that had once carried me into war and turned toward the van with the others. It was then Tim suggested I might want to go back and spend a moment alone with 038. I declined. The exertions of getting onto the wing had rekindled significant pain in my lower back and I needed to sit down. Also, I was feeling a measure of guilt about any more delay. I had already consumed Martin’s Sunday morning and keeping him any longer from his family didn’t seem fair.

But I couldn’t resist the gravity that the jet exerted on me. I stopped. “On second thought, Tim, I do want a moment alone with her.”

But I couldn’t resist the gravity that the jet exerted on me. I stopped. “On second thought, Tim, I do want a moment alone with her.”

The others stayed at the van while I backtracked. I stopped under the rear cockpit, placed my hand against her skin, closed my eyes and was instantly transported back to August 2, 1969….

I was 23 years old, thundering toward a photo target, a few hundred feet above the bomb-scarred terrain. My pilot and I were in our eighth month of war. We were pros, automatic in our actions, combat-wise.

The jet was unarmed, so we relied on our speed and low altitude to provide the safety that came with surprise…and always, we obeyed the first commandant of photo reconnaissance: One pass, haul ass. Regardless of outcome, we would not go back for a second pass.

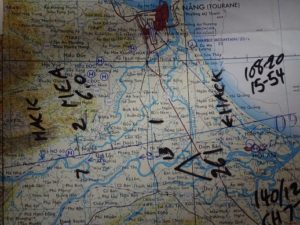

Was it a night or day mission? Into North or South Vietnam? Perhaps Laos. I don’t recall. But at three hours duration I’m reasonably certain it included multiple targets and an airborne refueling. I suspect it was a day mission into the northern part of South Vietnam, near, or in, the DMZ; or into an area of the Ho Chi Minh trail coming out of North Vietnam and into Laos. But it could have been a night mission. If so, we used the terrain following feature of the radar to insure ground clearance. I most feared night missions. Flying at low altitude and high speed at night in mountainous terrain is always something to fear.

But it could have been a night mission. If so, we used the terrain following feature of the radar to insure ground clearance. I most feared night missions. Flying at low altitude and high speed at night in mountainous terrain is always something to fear.

Regardless if it was a day or night mission, an elapsed stopwatch time from my final radar fix was my cue to activate the cameras. If a night mission, I had set the intervelometer to just five photos. The photo-flash cartridges…brilliant flashbulbs sequentially ejected from the aircraft…telegraphed our future position in the sky, placing us in danger from gunners on the ground. We hoped their reaction time was longer than those five flashes. We would disappear into the night in a turning climb at the instant of the final flash.

Other memories materialized: the pressure points of the straps fixing me to the ejection seat; the feeling of invincibility that came from being welded to the machine; the shriek of the engine air-starter; the smell of the jet fuel fumes; the salute of the crew-chief as we taxied from the revetment; the tightness of the mask on my face; the mind-clearing effect of the first inhalation of pure oxygen; the squeeze of the anti-g suit in a high-speed turn; the sweat being pulled from under my helmet to run in rivulets down my face; a line of anti-aircraft tracers passing too-near and the burst of adrenaline that comes with the experience; the radio and intercom chatter; the post-mission scan of our film on a light table and the elation of finding we had nailed a difficult target; the comradery in the barracks and O-club; the sights and smells of SE Asia.

The touch to 038 was brief, but it made it all so very real again. Tim had given me the most precious of gifts…the gift of time, of taking me back 49 years and making me young and vibrant again. It is a gift I will never be able to repay.

The moment ended, and I returned to the van. As we drove toward the boneyard exit, I thought of how many other aircrewmen and women were as connected to these machines, as I had been to 038. As Tim had written, ‘There is a certain relationship that military aircrew have with the airplanes they flew and specifically into combat.’ How many men and women could come to this graveyard, touch the plane they had once flown and relive their moments of joy and terror? Thousands of them. Virtually every aircraft I was seeing had logged decades of service. They had been flown in multiple wars and had outlasted the active flying careers of multiple generations of aircrews. 038 had been crewed by Baby Boomers in Vietnam and Generation Xers in the first Gulf War. (038 ended her service life with the Alabama Air National Guard. She was retired to the boneyard in 1992.)

This desert graveyard held the potential to energize emotions spanning the spectrum of the human soul. The most hardened pilot could be brought to tears here. Long-retired B-52 crewmen could be taken back to their Cold War missions, when they had feared this would be that mission…the one that ended with the release of a hydrogen bomb over an enemy city.

The U-2 pilot laying her hands on her aircraft might once again experience the boundless joy of flying in solitude at the edge of space.

Would helicopter crews relive the heartache of cleaning the blood from the floor of their craft after a combat medevac mission?

I can see the C-5 crewman recalling their time alone in tearful prayer among flag-draped metal coffins of KIAs being returned to America.

Other aircrews would once again see the smile of a child, as they lifted it aboard their aircraft or helicopter to be rescued from a humanitarian disaster.

The poltergeists of countless memories wandered this graveyard awaiting their crewmen/women to make them real once again. All it would take would be a touch.

I found it tragic to contemplate the fate of these glorious machines…to be recycled into soda cans and razor blades. 038’s stay of execution was probably lifted the day after my tour. As I write these words she has probably been reduced to a hash of metal, boxed for transport to the furnace.

But I found it even more tragic to envision the not-too-distant future, when the connection of man and woman to the machines of flight will no longer exist at all. How many decades before this boneyard is filled with nothing but drones, awaiting the guillotine of recycling? When that day comes, nobody will visit. Why should they? The machines of the drone-epoch will be soulless, bereft of any human attachment.

It was a thought which made me glad to have been alive for the incomparable experience of flight. Thank you, Tim Gagnon, for giving me the opportunity to relive that experience.

Post Script July 13, 2018:

Years ago my daughter, Laura, put me onto a terrific book: West with the Night, by Beryl Markham. Ms. Markham was born in the early 20th Century in Kenya, Africa and was an early aviation pioneer. She was the first person to fly the Atlantic Ocean from east to west. Below is an excerpt from her book which beautifully captures, in a poetry of words that I could never hope to compose, the deep connection of aviators to the machines of flight and how that connection is disappearing. She was prophetic. She wrote these words in 1942. (For brevity, I’ve edited out a few phrases where you see the ellipse: …)

“After this era of great pilots is gone, as the era of great sea captains has gone–each nudged aside by the march of inventive genius….it will be found, I think that all the science of flying has been captured in the breadth of an instrument board, but not the religion of it. One day the stars will be as familiar to each man as the landmarks, the curves, and the hills on the road that leads to his door, and one day this will be an airborne life. But by then men will have forgotten how to fly; they will be passengers on machines…and in whose minds knowledge of the sky and the wind and the way of the weather will be extraneous as passing fiction. And the days of the clipper ships will be recalled again–and people will wonder if clipper means ancients of the sea or ancients of air.” Beryl Markham, West with the Night